This biography was written by Clive Sowry and was kindly supplied by our friends at NZ On Screen.

Frederick Arthur O’Neill was born in 1919. Determined to make a living from art, he studied at an art school in Sydney after leaving Otago Boys’ High. In Australia he worked at an engineering firm. After war service with the RNZAF in the Solomon Islands, he set up his own company, Dunedin Electroplaters, a successful business that provided his livelihood while keeping up his interest in art through his hobby of oil painting.

After buying an 8mm movie camera, O’Neill began to explore the artistic possibilities of the medium. He joined the Otago Cine-Photographic Club, one of many amateur movie clubs thriving in the 1950s and 60s, and entered their competitions with some success (other names who began in the country’s amateur film club scene were producer Harry Reynolds, and NFU director Ron Bowie). O’Neill used 8mm film for his first experiments with animation. Short film Alphabet Antics, in which the silhouette letters of a word rearrange themselves to form an animated illustration of the word, won first prize in the club’s Cottrell Competition as it celebrated its 21st birthday in late 1958. His live-action film Sunday Idyll was runner-up.

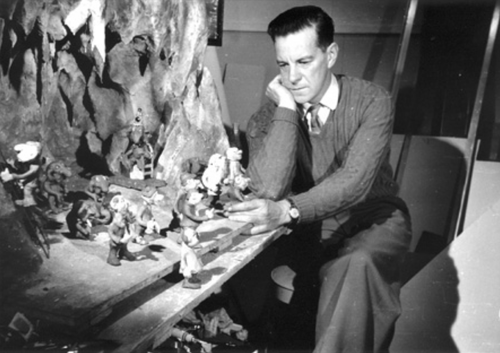

Soon O’Neill was animating shapes, animals and human-like characters – all moulded from Plasticine – to create inventive scenes both familiar and fantastic. Stop-motion animation (sometimes called claymation) required a lot of planning and preparation, and hours of frame-by-frame filming. For one early film, a hundred hours of patient work translated into eight minutes of screentime. Part of his home was modified and equipped as a studio for carrying out his animation work. Realising the limitations of 8mm he upgraded to 16mm, and mainly used colour film.

Hero image: Fred O'Neill on the set of the 'Enchanted Forest' with some of his plasticine creations used in his animations.

'Plastimania' - 1958

O’Neill achieved recognition overseas with Plastimania, as runner-up in the 16mm category of the British Amateur Cine World Ten Best Films of 1958 competition. In the following year’s competition he entered Phantasm, a longer animated Plasticine film, also in colour and with a soundtrack on tape. This film was selected as one of the Ten Best films of 1959, the first time a New Zealander had been so recognised. He repeated the feat the following year with Flight to Venus, and again in 1961 with Hatupatu and the Birdwoman. Having a film selected as one of the Ten Best three years in a row was a rare achievement.

O’Neill achieved recognition overseas with Plastimania, as runner-up in the 16mm category of the British Amateur Cine World Ten Best Films of 1958 competition.

Phantasm also won awards at the International Festival of Amateur Films in Cannes, and another amateur contest in Australia. Prior to this international success, Plastimania had attracted the attention of the National Film Unit’s South Island representative Frank Chilton. He saw potential in the technique of Plasticine animation to educate children through story-telling. The NFU pitched the idea to the Health Department and production began on O’Neill’s only 35mm film Space Flight, which was eventually completed in 1962.

Dan, the non-smoker hero of the story, is the only recruit fit enough to fly to Venus, where he frees the Venusians from the grip of the demon Nicotine. Despite being filmed in the professional gauge, distribution of the film was largely confined to non-theatrical screenings arranged by health educators. Three further films for the NFU were all shot on 16mm. For the transforming shapes and quirky characters in Plastiphobia (1964) he made good use of increasingly-hard-to-find Plasticine, while for the animated Māori legends, The Great Fish of Maui (1967) and Legend of Rotorua (1967), the puppets were made from a plastic compound known as vinagel.

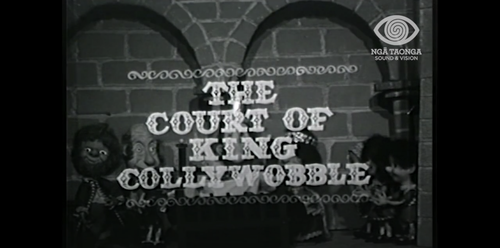

The Court of King Collywobble - Framegrab of the popular animated puppet series

It was only through the movie clubs and cine societies that O’Neill’s films could initially be seen (although eventually five of his films were available through the National Film Library). Highly valued and respected by his fellow amateur film makers, O’Neill’s advice on film and animation techniques was much in demand. Technical advisor to the Otago Cine-Photographic Club, he also served as its president. During a talk at 1962’s tenth annual conference of the Federation of NZ Amateur Cine Societies, O’Neill screened his films, plus another film showing how they were made.

O’Neill’s special skills were sought out by the NZBC for some early children’s programmes produced by Dunedin regional station DNTV-2. Most well-remembered were the thirteen films in the popular animated puppet series The Court of King Collywobble, which featured in Junior Magazine from Dunedin (also known as After Five) in 1965. Although aimed at children, such was the interest in King Collywobble that the NZBC made a film about O’Neill’s work for arts show Focus.

'Focus on Fred O’Neill Film Animator' - Interview with New Zealand film animator Fred O’Neill

In 1966 he made TV series The Space Twins, featuring characters Rod and Dawn. Television brought his work to a large new audience, but it was an audience whose expectations were heightened through exposure to popular TV programmes from Thunderbirds producer Gerry Anderson, which used the sophisticated puppetry technique Supermarionation.

The 1967 death of Nancy O’Neill, Fred’s wife and fellow amateur film maker, seems to be the point at which he abandoned film making as his principal hobby. He reverted to oil painting and served as President of the Otago Art Society, and held office in a number of other organisations .As a candidate for the National Party he stood unsuccessfully for the Dunedin Central seat in 1972, the same year he sold his electroplating business. After a short illness, he died at his home in Dunedin on 28 June 1985. He was 65.