By Dr Leslie Lewis & Diane McAllen

This blog was originally written for a Christchurch screening of A Daughter of Christchurch on February 17 2018. It was part of the annual Sparks event in Hagley Park. It was the first time in 90 years that the film was seen in its original tinted colour format.

Although not widely known, films from the silent era were more likely to be coloured than simply black-and-white. Filmmakers used a variety of processes to colour the nitrate film stock, including tinting, toning, hand-painting and stencilling.

With A Daughter of Christchurch, a black-and-white image was printed onto pre-coloured stock. From the mid-1910s through to the 1940s, film companies such as Kodak, Agfa and Pathé sold film stock pre-tinted in a wide variety of colours ranging from pale pink to midnight blue – and every hue in-between.

Audiences of the period would have been familiar with this cinematic shorthand, knowing how different colours were used to signal changes in time or convey emotion. For instance, blue was often used for night scenes, red for fire, green for jealousy or in New Zealand, bush scenes.

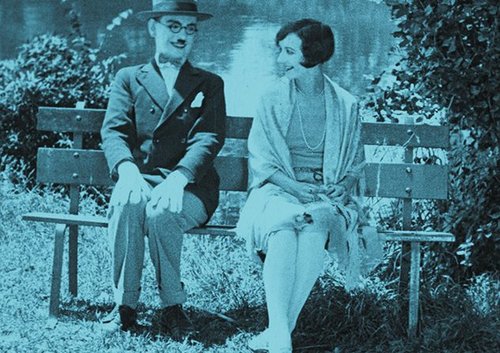

Hero image: Still from the silent film 'A daughter of Christchurch' (1928).

Still Frame - Don Harvey as Bill Cowcocky amongst locals in a scene from A Daughter of Christchurch (1928).

Unfortunately, many of the dyes used to colour the films proved unstable, fading away over time – sometimes taking the image with it. The effects achieved using the original chemical processes can be difficult to exactly replicate with digital processing. However, our trained preservation specialists are always refining their methods in an effort to duplicate the colours as closely as they can.

A Daughter of Christchurch is one of 23 “community comedy” films made in 1928-1929 in cities and towns across New Zealand. The plot was taken from a standard script, A Girl of Our Town, copyrighted to Rudall Hayward, with local cast and locations added for each production. These films followed a model established in America and Australia, large audiences being virtually guaranteed as locals queued to see themselves on the big screen.

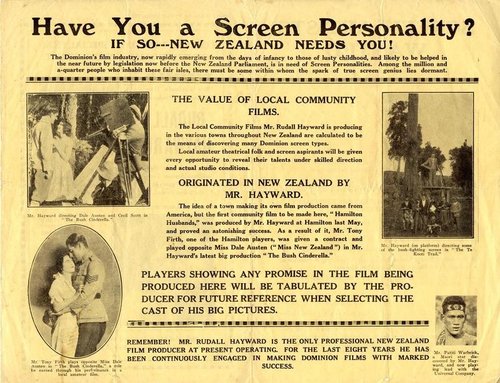

At a time when New Zealand interest in the pictures were fueled by the Hollywood star system, young women and men were enticed by the filmmakers to be the next heroine or villain. Advertisements in local newspapers called for:

“A Young Lady with good even features, dark eyes, good teeth, slender and graceful to fittingly represent the heroine. A Typical N.Z. Outdoor Man, able to ride well. A Smart Man-about-town, well dressed, able to drive a car. A Number of Young Ladies for Special Scenes and A Number of Good Local Riders With Their Own Horses”.

The film provides an opportunity to glimpse Christchurch of 90 years ago and the fantastic fashion of the late 1920s era. There is also some interesting local flavour. Each of Hayward’s community comedies incorporated a few local variations, and the Christchurch variant has references to dangerous traffic intersections, with the chase scene taking place on bicycles and not horseback, and an intertitle asserting that “Christchurch girls would rather take a punt on the Avon than go home by motorcar” – hardly surprising for a city once known as “Cyclopolis”.

Circular for performers to appear in Rudall Haywards films: NZ Museums Object: D0516 13/1

The filmmaking process behind the Daughter of… films is a tale in itself. Each had a quick turnaround: filmed in a few days, developed, submitted to the censors office and then up on screen within two weeks. These films invariably have a few rough edges. As Rudall Hayward noted, they only needed to be “moderately good” to generate decent box office. Money made from ticket sales helped finance the next film in the next town.

Hilda Hayward (Rudall’s business partner and first wife) would already have gone ahead, securing locations and auditioning locals for the parts of the School Teacher, Freddy Fishface and Bill Cowcocky. The film crew’s subsequent arrival and filming in the town would draw curious crowds at a time when movie cameras were still a novelty.

Daughter of Christchurch was one of the most popular of the Haywards’ “community comedies”: it ran for a season of two whole weeks! “You couldn’t keep them out of the theatre with iron bars” recalled Rudall Hayward in a 1962 interview.

The formula was so lucrative that, following a dispute between Rudall Hayward and another collaborator, Lee Hill, during the filming of Natalie of Nelson, Hill absconded with the script and went on to produce his own versions in neighbouring towns. This including the rival production Nellie of Nelson. Unfortunately, only five of the 23 New Zealand “community comedies” made by Hayward or Hill have survived to the present day.