Beginning

In February 2021, I was taken on as an intern at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision due to my established working relationship with Dame Gaylene Preston. I had been her personal assistant over the past five months, my work often veering into archival territory. By familiarising myself with the intricacies of her career and organising some of her personal digital archives, I had naturally gained a lot of relevant content knowledge.

With financial support from Balanced Investments and me in tow, Gaylene approached Ngā Taonga with a question she hoped could be answered: ‘How do you solve a problem like Gaylene?’

Boasting hundreds of unique titles and over 2,000 material items deposited across four decades, Gaylene’s collection is one of the largest of an individual’s work in the entire Ngā Taonga archive. It is also remarkably diverse, covering feature films, documentaries, shorts, commercials, and television series; all built from innumerable audiovisual formats and material types. Much of it is also complex and disorganised, full of cul-de-sacs and avenues that are difficult to navigate. Approaching this collection with the aim to look over it all and produce a high-level database analysis was no inconsequential task.

Beyond the scope and size of Gaylene’s collection within Ngā Taonga, there are many other reasons why she was selected as the first figure that we attempted this kind of project with. 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the first short film that Gaylene ever made: an approach to art therapy with several of the patients from Fulbourn Mental Hospital in Cambridge, England. Since then, Gaylene has directed 23 other short films, 11 features, and three television series. She is credited on a further 25 national productions.

Celebrated as a key supporter of local media, independent film productions, and the first-ever filmmaker to be named a Laureate by the New Zealand Arts Foundation, Gaylene’s significance as a representative of New Zealand film cannot be overstated. In 2019, Gaylene was appointed a Dame Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her services to film.

Gaylene is also a long-standing friend of the Archive, being a member of the initial New Zealand Film Archive board in 1981 and a serious advocate for the importance of archival film and its accessibility. Many of her own projects incorporate archival film sourced from Ngā Taonga and other repositories, further proving the importance of their continued preservation.

Thanks to the unique position we found ourselves in with this project, the typical uncertainties surrounding preferred sound mixes, incomplete credits, master material and rights clearance were made irrelevant. All questions and concerns could be directed to Dame Gaylene herself, allowing our decisions to be approved by the filmmaker, depositor, and rights holder with ease. Through conversations and updates I shared with Gaylene, I was able to clear this work as I did it, operating with certainty in a way few other archivists are able.

We could confidently say that the vast majority of this collected material was going to remain significant and worthy of housing, but much of it was difficult to discover and properly unpack. By tasking me to delve into this collection, I was being handed the opportunity to make a difference and allow more people the chance to experience these wonderful films. Before I knew it, I had been welcomed into Ngā Taonga, given the appropriate training, taught to navigate the database, and sent on my way.

Emma Richardson and Danny Bultitude organising the deposit of Gaylene’s material

Photographer: Gaylene Preston.

Sifting

Right from my first day working at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision, I found it wonderfully rewarding to be part of an organisation that championed those beautiful, intangible concepts of future and past. Here is history being ensured a life beyond its material reality, ensured a viewership by generations to come. To know my work could increase the likelihood of Dame Gaylene Preston’s filmography reaching this outcome was very moving and encouraged me to approach this project with my eyes open to every possibility.

After generating a spreadsheet containing a list of the many items deposited by Gaylene over the years, I began my manual search. To guarantee that this spreadsheet was comprehensive and contained all the relevant material details, I conducted searches for every individual film title I encountered, checked over every item that made mention of the words ‘Gaylene’ or ‘Preston’ and looked over the referenced deposits made by people other than Gaylene, just in case they contained material I had initially missed. Due to the 35 years of deposits that came together to build this collection, it offered a fascinating sample of the changing approaches, methods, and kaupapa of Ngā Taonga as well.

Once both Gaylene and I felt confident in the comprehensiveness of this spreadsheet, I looked over other repositories that could hold material pertaining to Gaylene, including the Alexander Turnbull Library, Archives New Zealand, and the British Library. Although some offered very little additional material, the experience forced me to fully understand the vast scope and incredible depth of this collection for the first time.

This spreadsheet became a useful tool for compiling the data and considering what organisational methods worked best for the collection. By undertaking this database analysis and cross-referencing it with some pre-established timelines of Gaylene’s career, significant gaps and over-stuffed points revealed themselves. Points of imbalance were made obvious, suggesting the future selection and deselection work that could remedy these issues.

Having already downloaded and organised the relevant data, my focus shifted to the creation of a central reference point, which could present this data in a useful and intuitive way. Several ideas were considered, including a catalogue raisonné and a database evaluation. Senior Collections Archivist Emma Richardson and I eventually came to an agreement that a comprehensive, user-friendly ‘finding aid’ was the most appropriate goal to aim towards.

From Gaylene Preston’s personal collection.

Finding

A finding aid is an archival tool that acts as both guide and inventory to the contents of an archival collection, helping researchers to navigate and understand the collection while streamlining the internal process for staff. Due to content privacy restrictions and the way Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision operates, a lot of the hyper-specific information I gathered could not be shared with the public.

This ultimately proved to be beneficial to the development of this document, as it allowed us to experiment and radically alter the expectations around the often unintuitive and over-formal nature of a finding aid. We came up with the idea to split the document in two: one public-facing and entertaining, the other internal and practical.

The internal document more closely resembles the blunt, pared back, and material-based finding aids commonly used in archives, whereas the public document is a deliberate departure from this method. The public-facing document adds much more colour and context, including descriptions of the films, contextual quotes from Gaylene, award information, and photographs. Direct comparisons can be made between these two documents, with Ngā Taonga staff able to find the reference numbers, material details, and metadata only alluded to in the public-facing version.

The public-facing finding aid is currently live, and accessible through the link below. It is the most comprehensive catalogue of Gaylene’s filmography currently available and has been designed with researchers and interested members of the public in mind. It remains a living document, with the potential to be updated as new material is accessioned or deselected. I encourage you to give it a look.

The Dame Gaylene Preston Legacy Collection Finding Aid v1.1

Download Finding Aid Public - PDF -V1.1 – PDF, 1016.5 KBListening

Throughout this entire process, I was continuing my work as Dame Gaylene Preston’s personal assistant for a day or two every week. Together, we organised the massive personal archive within Gaylene’s home, conducted research for funding applications, and curated photographs for Gaylene’s Take: Her Life in New Zealand Film – a memoir to be published by Te Herenga Waka University Press on November 10, 2022.

I spent much of this time listening to the Dame, bathing in her knowledge and enthusiasm, gasping as she recounted her remarkable experiences. So much wisdom, humanity, and creativity surrounds Gaylene, and I constantly caught myself writing down quotes and taking cues from her. With every minute of conversation, I better understood the collection and the films within it – even if they were not the topic of conversation. I knew these words were just as worthy of preservation as the information I had researched, and I knew how best to capture them.

Recorded over four sessions between 29 October and 8 November 2021, the oral history we made together is a beast. Coming to 281 minutes (with an additional hour of audio recordings designed to capture the quotes needed for the finding aid) and allowing Gaylene to comment on a series of questions focused on archival practice, legacy, memory, and the passage of time, this oral history succeeded in preserving a piece of the filmmaker alongside her work.

I approached the interview with the intention that it would not only provide illuminating context for Gaylene’s oeuvre but also act as a guide on how she wants her collection to be cared for and represented in the future. Many questions directly relate to preferred ‘director-approved’ versions of films, supplementary pieces she considers standouts, and the ways she would like her career to be remembered. Although not intended for public viewing, this oral history will remain safely with Ngā Taonga, a guiding light for the next generation of archivists and researchers who encounter Gaylene’s work.

By listening to Gaylene’s opinions surrounding her own collection, I began to see it differently. She noted her fondness for ‘the 5-hour compilation of Making Utu’ which could have easily been mistaken for wild footage, ‘a collection of Mr Wrong script assessments’ that I had already considered flagging for deselection, and the dozens of home movies in her collection. Pointing out the specific titles she had made ‘as complete, edit-in-the-camera pieces that weren’t for mainstream exhibition,’ Gaylene acknowledged that these home movies were essentially ‘sketches [leading] towards paintings, the features being the paintings.’ These pieces are fascinating and elucidatory but cannot thrive outside of an archive due to their ‘unofficial’ quality.

Material that could have easily been dismissed or fallen by the wayside was given new life by this oral history, being highlighted by the filmmaker herself as material of worth. Similarly, Gaylene provided information on two short films she directed in the 1970s, Creeps on the Crescent and Whose School? which appear to be lost. With Gaylene posing her own assumptions and thoughts of where they could be, we have more information than we have ever had on these pieces before. Although it can be easy to lose faith in uncovering a lost film, Gaylene remains hopeful, noting the undeniable truth that ‘Everything’s gotta be somewhere!’

The process of recording this oral history afforded Gaylene the opportunity to take control of the future. By providing this platform to an artist, we can return this power to them and let them use their own words to define themselves. There are numerous examples of artists and creatives being misrepresented or miscategorised after their deaths and this is another method to safeguard against that. Gaylene shared a story relating to this in the recording of the oral history itself:

‘I’ve never Wikipedia-ed myself and I did the other day. I can’t remember why, but I did. And it says “has a special interest in documentary.” The problem with that is I don’t have a special interest in documentary. I have a special interest in storytelling, and I’ll use whatever medium’s right for that . . . so I would like that changed.’

Through conversations like this, we can know what terms to use and which to avoid. Across the oral history, I also presented Gaylene with quotes taken from earlier interviews to find out if her opinions have changed at all, thus making certain the information available is up to date. Gaylene also noted that this project has allowed her to consider which pieces are her primary works and prioritise them accordingly.

‘It’s actually liberating doing this,’ Gaylene told me in one recording. ‘Because I think: Oh well that’s good. I could die and it’d be alright.’ Earlier in the oral history, Gaylene had revealed that this project was born in the nanoseconds before she lost consciousness from a head injury. Facing her own mortality, Gaylene saw the immensity of her disorganised collection and how it could become a huge burden on the people she loves. Through this project, we have assuaged that fear entirely, organising everything we possibly can and leaving it well-signposted. With the addition of this oral history, I believe we have succeeded in preserving a piece of Dame Gaylene Preston alongside her films.

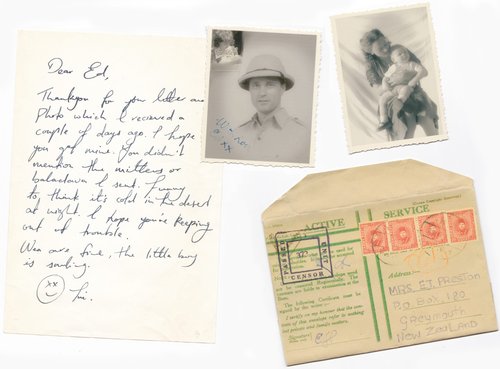

A scan of the Home By Christmas ephemera

Provided by the filmmaker.

Closing

There was a wonderful moment early in this project, when I was building a list of all the film-related material stored in Gaylene’s home. We concluded that many of the gaps I had identified during the database analysis could be filled with a new deposit to Ngā Taonga, and this was a good first step in the selection process. I came across a small box containing many old telegraphs, envelopes, handwritten letters, and black-and-white photos, seemingly written by Gaylene’s father Ed Preston during World War Two. I classified them as ‘personal’ and moved along.

Only after Gaylene handled this ephemera did I notice that the person photographed was Martyn Sanderson in character as Gaylene’s father for Home By Christmas. All of the letters and materials were screen-used facsimiles of real documents made by the production design team, practically identical but dating to 2010 instead of 1940. Without Gaylene there to assist, these items would have remained mislabelled and there would have been no reason for me to doubt the veracity of it.

This is a shrewd little example of a real problem facing our material history. Without the context only known by creators and kaitiaki, how can we consider our assumptions to be correct? Without the proper context, how useful can this material be? The physical items are taonga, but so is the knowledge that surrounds them. I believe that we have succeeded in capturing both during this project.

A new deposit of material for this collection is currently being evaluated, the selections made to fill significant gaps in what is currently archived with Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision. There is now a backbone which this material can be placed upon, a timeline everything adheres to, an overarching philosophy that’s visible from every corner.

‘How important our little footprints are to others is for others to decide really,’ Gaylene said to me during the recording. ‘I’m just glad that, from this legacy project, it’s there. If they wanna ignore it? Fine. I don’t care. I care that it’s there. [It’s there] in a way that people who want to pay attention don’t find too difficult to follow or access.’

This is a wonderful feeling, the undeniable beauty of archiving. We can all bask in the comforting assurance that it is there. A simple, earth-moving statement. It is there. History remaining present. History kept safe.

Dame Gaylene Preston

Image from a recorded oral history of Dame Gaylene Preston.