By Heperi Mita

I think I was only about 4 years old when he blew up a house in Ponsonby, but that’s the kind of thing that leaves an enduring impression on a young boy.

When I was 6 years old, he took me out to the middle of the Nevada desert where he was shooting a robbery scene for the HBO movie The Last Outlaw. This time he blew up an entire bank.

By the time I was 8, he was orchestrating a head on collision between two freight trains in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado for the Warner Brothers film Under Siege 2: Dark Territory, and it was at this point it struck me to ask him a simple question: “How did you get your job?”

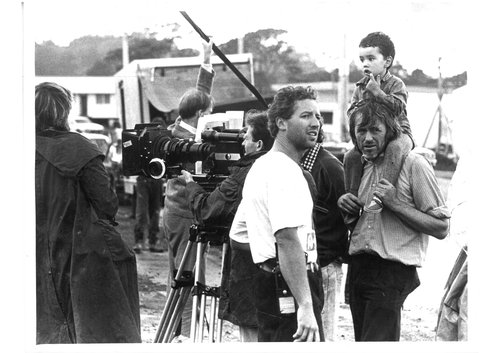

Hero image: Geoff Murphy on-set with his son, Heperi Mita, on his shoulders.

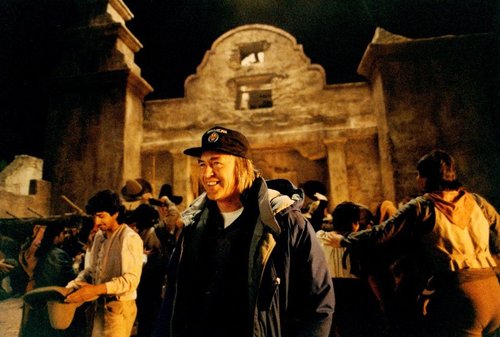

Geoff Murphy on the Young Guns II film set.

Even as a young boy I recognised the prestige of his position as a director on set, but aside from the opportunity to blow things up, the glamour meant nothing to him.

While filming in London with Tom Skerritt, Helen Mirren and Max von Sydow on Red King White Knight, the thing he talked about the most were the home videos he took with my brothers Bob and Miles goofing around in Europe.

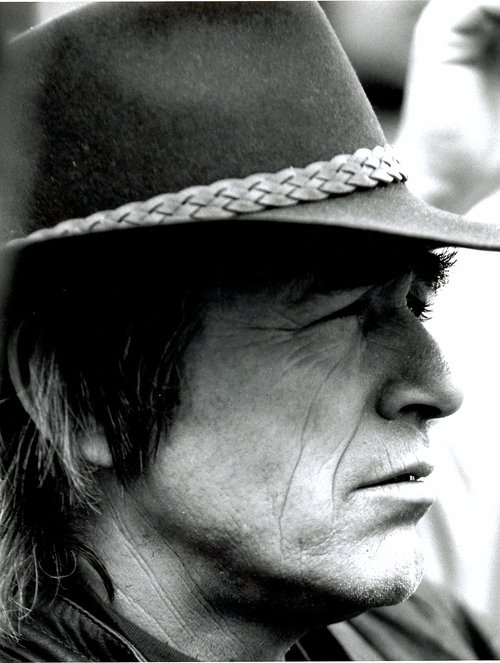

He was 47 years old and greying by the time I was born, so my mental image of him has always been of him as a grizzled old director puffing on a cigarette. It is through the archives that I get to see him as a young man, a time the preamble to Goodbye Pork Pie describes as “an almost forgotten age, the good old days when you could drive your car whenever you pleased, and gas was less than a buck a gallon.”

And what I see in those old films are a bunch of mischief-makers picking up a camera and having a bit of fun, while under the influence of some sort of mind-altering substance.

A man whose passion for the trumpet and notoriety as a hippy far eclipsed any notion of him ever becoming a successful director.

But you can also see the raw cinematic instincts of the filmmaker he would become, and the playfulness that he carried into his later work. He would make his flippancy his signature and it comes across in his Kiwi classics.

It’s an aspect of his style that gets toned down significantly in his Hollywood work, and I guess those home movies with my brothers were his outlet to express that side of him.

But despite his reputation for having a laugh and indulgence, he took his craft seriously. While he once told me he couldn’t count the number of times he did acid, he also said he never did any of his professional work under the influence of any kind of substance. And he was uncompromising in his principles.

I remember on the set of a Western he was filming in the States there was a scene set in a Mexican village involving hundreds of extras, the majority of whom were elderly women. The Second Assistant Director, pushing to complete the shoot on schedule, mercilessly barked orders at these kuia, and upon witnessing this my father reprimanded him in front of the entire crew and questioned the Assistant Director’s sense of decency and respect. And while dad was never the most aggressive man, the memory stands out to me because I had never seen someone so ashamed as that Assistant Director was.

There are many things that I see in him which he has held steadfast throughout his life. But as he’s aged I’ve also seen him change.

He retired from the film industry more than a decade ago. He quit smoking when he turned 70. He also doesn’t drive anymore, a big adjustment for the man who once drove a stunt car into a lake for Goodbye Pork Pie.

Time and the cumulative effects of his indulgences have wearied his body, and outliving many of his peers and close friends has softened him emotionally. To be completely honest, the thought of his mortality is a topic that weighs heavily upon the minds of those of us who are close to him.

But that has been the case for some time now. I remember going to the pub with him a few years ago where he was greeted by Dave Gibson who joked: “Jesus Christ, Geoff! You’re still alive!”

Well my father turned 80 a few weeks ago, and even he is surprised by his own longevity.

There was a time not long ago when he thought he’d never live to see his work properly recognised – a lifetime as an anti-authoritarian did not exactly ingratiate him with the gatekeepers of society. But in the past five years he has been awarded almost every accolade one could achieve in film – from lifetime achievement awards, to being named an Icon of the Arts.

And so the journey into old age is bittersweet. But the beauty of such a long life in film means that the past is only as far away as the play button.