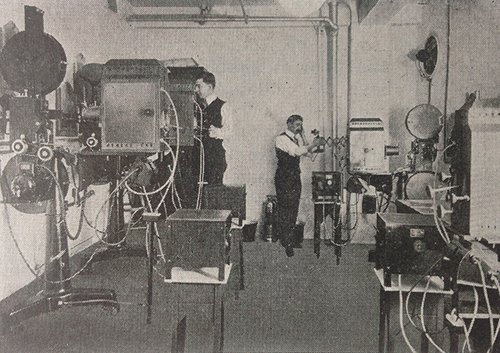

Above image: Projection room at Pathé’s American headquarters - published in F. H. Richardson's 'Motion Picture Handbook: A Guide for Managers and Operators of Picture Theatres' (Third Edition - 1915)

By Ellen Pullar (Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision)

This post belongs to a two-part series. Read the second part, Projecting Film Today – an interview with Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision Projectionist Oscar Halberg.

What was it like to own a movie theatre in 1915? How were films projected 100 years ago? In today’s rush to embrace digital cinema projection, the act and ritual of handling physical film during projection is becoming something of a lost art (fortunately though, film archives around the world remain dedicated to projecting on film – the Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision cinema is equipped to project both 35mm and DCP – Digital Cinema Package). Call me nostalgic, but for me there’s nothing like watching a film that by its very tangibility evokes its conditions of production and exhibition – the “cigarette burns” that mark where one reel of film is about to run out, or usage scratch marks that testify to the enjoyment of the film by the audiences of a previous generation. The third edition of F. H. Richardson’s Motion Picture Handbook: A Guide for Managers and Operators of Picture Theatres, suggests that the craft of film projection had already developed to a high level of sophistication by 1915, when this edition was prepared.

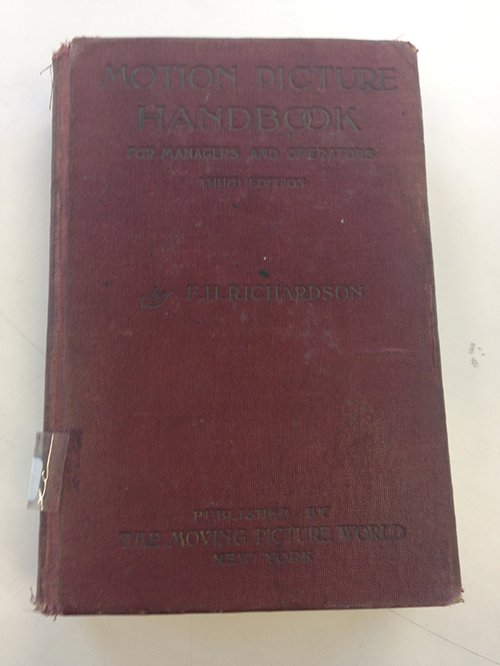

F. H. Richardson's 'Motion Picture Handbook: A Guide for Managers and Operators of Picture Theatres' - Third Edition, 1915 (This copy is housed in the Jonathan Dennis Library at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision Wellington)

This handbook is housed in the Jonathan Dennis research library, accessible by appointment at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision Wellington, where it sits alongside a diverse range of books relating to film and television production, exhibition and reception, dating back to the late 1800s. I immensely enjoyed reading the Motion Picture Handbook, even though some of the detailed electrical, scientific and mathematical information contained within far exceeded my limited comprehension in these fields. The author Richardson’s encyclopedic knowledge of every aspect of film projection and movie theatre ownership is most impressive. He considers everything – electrical wiring, amperage, rheostats, how to avoid short circuits, alternating currents, arc rectifiers, the pros and cons of different kinds of lenses, the science of light reflection, persistence of vision, how to care for a range of different brands of film projection equipment / tools / electrical equipment, how to look after and repair film, making your own advertising slides, the colour and intensity of projection lamps, ways of laying out and furnishing cinemas, the ideal dimension of the space between rows of seating, cinema lighting schemes, what type of neighbourhood to build your cinema in, what sort of personages to hire as staff, and a lot more in-between.

The Jonathan Dennis Research Library - Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision Wellington

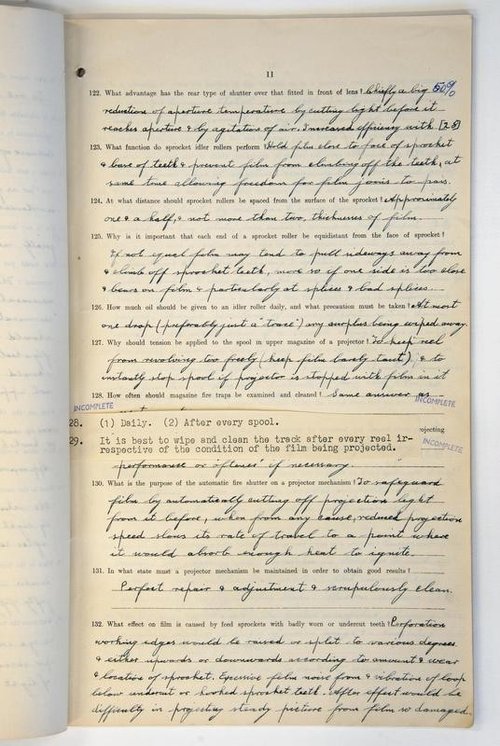

This particular copy of the Motion Picture Handbook book was originally owned by Caleb Wyatt. Wyatt was the projectionist at New Plymouth’s Regent Theatre during the 1940s and 1950s – although some of the technical information inevitably dated, the fact that the information wasn’t considered to be wildly out-of-date by that time is suggestive of the strength of Richardson’s knowledge and practical experience back in 1915. As well as being a projectionist, Wyatt was an avid maker of home movies, and enthusiastic about all things cinematographic. The Motion Picture Handbook was likely a valued possession amongst his collection of cinema books, perhaps he drew upon it while studying for his Cinematograph Film Operators Licensing Board Examination in 1938.

Cinematograph Film Operators examination paper (1938 – 1939), completed by Caleb Wyatt - Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision Documentation Collection

The breadth and technicality of the knowledge encompassed within the comprehensive, 702-page-long Motion Picture Handbook is suggestive of the very real need for projectionists to be suitably qualified. In fact, the handbook contains a section on the American Operator’s License [pp. 617-22], which was a legal requirement in many states at the time of publication.

Below are just a handful of the subjects on which motion picture projectionists and mangers were expected to be knowledgeable (for the full, and rather more extensive, range of subjects covered, refer to the book – the Media History Digital Library have made the full book available for browsing online.

The Screen and Projecting

According to Richardson, the preferred surface on which to project is a matte screen, which “enables the eye to see the picture more clearly and in greater detail when viewed from a side angle.” He notes, however, that in small towns plaster walls or sheets “made of reasonably good grade muslin” are often used, and these are quite acceptable [pp. 169-171].

For well-resourced cinemas, there is the option of investing in metallized or mirror-backed screens, which have the added benefit of greater “brilliance of illumination” [p. 173].

Another option to consider is a transparent screen, onto which the image must be projected from behind. Richardson notes that transparent screens are usually employed as makeshift because of the distance required from the back of screen to project. “If a cloth screen be used the result will be greatly improved if it is kept wet with water,” he advises [p. 174].

On the trend then current for tinted screens he exposits:

“At this writing (last half of 1915) it is very much the fashion for screen manufacturers to tint the surface of their screens. Some manufacturers put out several surfaces, such as plain metallic, flesh tint, faint yellow, etc. The author is not in accord with this practice. […] he does not believe there is anything so beautiful as the plain black and white projection, with a pure white light and nearly as possible a pure white screen surface. The only tinting he believes in is the addition of a little blue to the while when mixing a screen paint or calcimine, this being for the purpose of rendering white painting still more white, just as the laundryman adds bluing to the rinsing water in order to make clothes more white” [p. 178].

All screens must be stretched tightly, using frames, so surface wrinkles do not interfere with the picture.

He discusses projection lamps on the market in detail. Eager to provide a guide that is of value to the largest, most lavish picture palaces, and tiny small-town theatres or itinerant travelling shows alike, he also discusses projecting by limelight in lieu of electricity. Projecting by limelight (“directing the flame of hydrogen mixed with oxygen against a pencil of unslacked lime”) is a decidedly less desirable option, because the projected image is less bright: “Those who by force of circumstances are compelled to project moving pictures with limelight will be well advised to select films of the least possible density and not attempt the projection of a large picture” [p. 674].

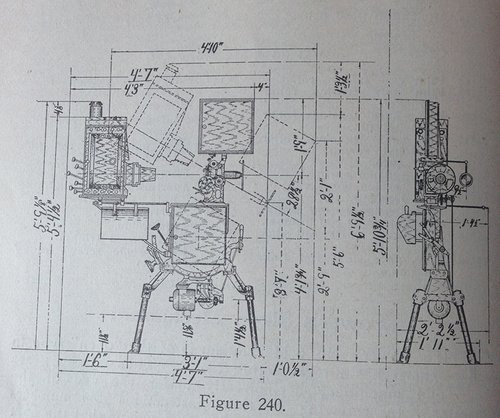

A Power’s Six-B Projector - Motion Picture Handbook, p. 492.

Fire Precautions

Nitrate film stock, in common use at the time, is notorious for being inflammable. Richardson advises that design of the projection room and layout of the theatre incorporate multi-tiered measures to minimize damage in the case of a fire (although following his careful instructions for handling film / machinery and laying out the projection room would significantly reduce the risk of a fire). Hollow tile, concrete, and brick are given as the most fireproof materials to construct a projection room from, with the addition of fire shutters on all ports and doors [p. 211].

“If the operating room be rightly constructed, equipped with a proper vent flue and has a properly arranged shutter system you can burn several reels of film therein and the audience will never know there is a fire” [p. 178].

In the eventuality of a fire, he recommends removing the “sticky, brown colored gummy sediment” left on projection equipment by using peroxide of hydrogen [p. 208].

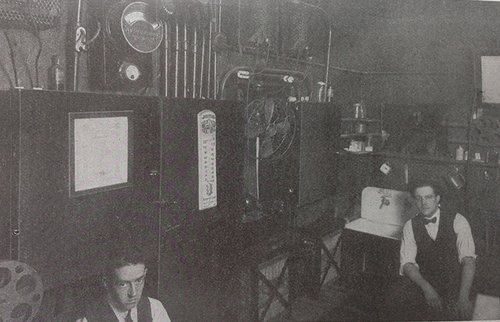

The projection room at the Monarch Theatre, in Clevland, Ohio - Motion Picture Handbook, p. 247.

Film Care

Richardson impresses strongly upon the reader that it is the responsibility of every projectionist to carefully look after film on loan from the film exchanges:

“It should be a point of honor with each operator to send the films away in as good condition as they were received. DON’T leave it to your brother operator who gets them next, to repair the damage you do. You are in a position to ‘pass the buck,’ true, but it is not a very manly thing to do” [p. 201].

He complains that the exchanges themselves often do a poor job of repairing film:

“In many exchanges men or girl inspectors are employed, at low wages, and are expected to ‘inspect’ anywhere from fifty to seventy-five reels of film a day, which is from two to five times (dependent on condition) as many as they can inspect and repair properly ” [p. 201].

(A prejudice against “girl” employees, a new and unfamiliar figure in 1915, is an ongoing theme of this book.)

The Motion Picture Handbook contains detailed instructions for repairing any “injury to the film” that might occur (Richardson’s use of humanizing language here reinforces his deep passion for film) [p. 195]. He includes instructions on: how to fix broken sprocket holes, what to do about tension issues and film stretching, how to avoid scratches (“nine-tenths of the scratching of film is due to poorly designed projector take-up tension and to ‘pulling down’ in rewinding” [p. 194]), how to rescue film if it is accidentally submerged in water, and how to patch torn strips of film back together.

He gives several formulas for film cement, which can be used to join torn pieces of film together again after the ends have been properly prepared. For non-inflammable stock, he recommends “one-half pound of acetic ether, one-quarter pound of acetone merch, in which dissolve six feet of non-inflammable film from which the emulsion has been removed” [p. 197].

If film becomes dry and brittle, his advice is to give it a “glycerine bath”:

“Make a drum of slats about six feet in diameter by about six feet long (for one thousand feet of film), and by revolving the drum draw the film very slowly through the liquid, winding the drum with the emulsion side out” [p. 204].

The drum shape ensures that the film is not stretched in drying.

He instructs his projectionist readers that it is essential to include a leader and a tail piece of at least four feet of opaquely exposed stock on every reel of film. This is because “in threading into the takeup it is frequently desirable, if not necessary, to fold an inch or so of the end of the film over itself,” also because “when the job is done, the end of the film often flaps around anywhere from one to a dozen times before the reel stops revolving, and if there be no leader to receive the brunt of this rough treatment the title is injured” [p. 199].

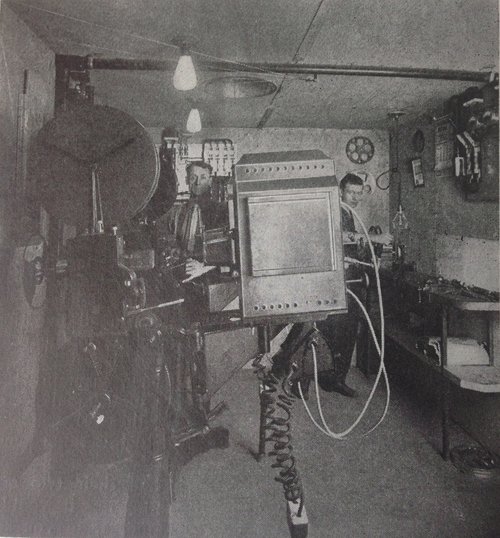

The projection room at the Park Theatre, Bangor - Motion Picture Handbook, p. 244

Making Your Own Advertising Slides

Motion picture projectionists and managers needed to know how to how to create their own glass slides – both for advertising use, and for relaying messages to the audience in the instance of an emergency. Richardson suggests that in the case of an emergency, the projectionist use special pens to write on glass slides messages such as “Unavoidable Delay of Two Minutes” [p. 643].

He also outlines several methods for creating professional-looking cinema screen advertising on glass slides through photographic processes – either by using a negative to make copies (to add to the scientific / chemical knowledge relayed elsewhere in the handbook a developing formula is given) or by direct positive printing [p. 614].

The direct positive method is as follows:

“If only one copy of a slide is desired, it may be made by writing on a white card with perfectly black ink, reversing the plate in the holder and stopping the lens down to make up for focus thrown out by reversal of the slide, and exposing. The slide will then develop white letters on a black background and be ready for finishing, the same as a contact print from a negative” [p. 614].

Richardson recommends the use of a book of architect’s alphabets for lettering, and notes that “too much ornamentation is a detriment, the plain slide being more pleasing and understandable than one containing an access of ‘gingerbread'” [p. 613].

Slides can be imaginatively coloured by painting onto them using velox water colours (interestingly, Richardson recommends applying a film of saliva to glass slide covers and letting it dry before painting over top of it) [p. 616].

Newspaper images or comics can be transferred to slides by placing carbon paper on the glass and then tracing the outlines. Alternatively copies can be achieved by varnishing a slide cover glass, then lying a newspaper clipping on top of it for 24 hours until dry, then soaking in water – the paper will dissolve, but the ink will remain [p. 616].

Knowing Your Audience

Richardson recognises the cinema as the democratic form of entertainment that it was (especially in comparison to the theatre, the price of which was prohibitive to many):

“Moving picture employees should have carefully impressed upon them the fact that merely because a patron wears a threadbare coat, or a cheap dress, is no reason that he or she is not entitled to receive exactly the same degree of courtesy shown the man or woman dressed in fine raiment.” [p. 663]

He also mentions romantic courtship rituals, suggesting that the Saturday night movie date was already well-established:

“When Willy Boy takes his inamorata to the show he will swell out his manly chest and buy two loge seats. It costs him 20 or 30 cents extra and is worth at least five times the amount to him in gratified pride.” [p. 643]

One of the things impressed upon me throughout the Motion Picture Handbook was the level of Richardson’s perfectionism for his craft. I’m going to end with some of the motivational plates that are scattered throughout the book, intended to inspire projectionist readers to aspire to his own high standards of film presentation.

Excerpt from the Motion Picture Handbook (p. 4)

Excerpt from the Motion Picture Handbook (p. 283)