Preserved by Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision.

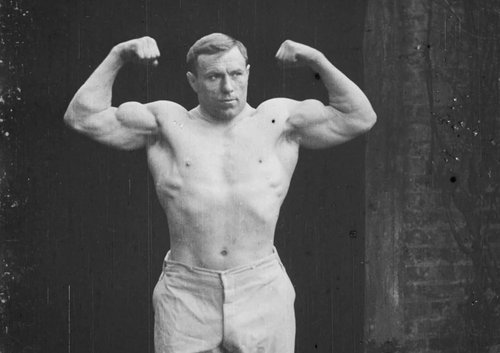

Hero image: screengrab of George Hackenschmidt from Hackenschmidt vs. Rogers.

The film preservation team at Nga Taonga recently completed the digital preservation of a very rare nitrate film. It is believed to be the only surviving copy of a recording which was made by the UK’s Charles Urban Trading Company in early 1908 and depicts a wrestling match between Joe Rogers and George Hackenschmidt at the Oxford Music Hall in London. This footage is now available to watch online, allowing modern day fans to see Hackenschmidt in action for the first time ever.

George Hackenschmidt, the star attraction (1877 – 1968), was one of history’s best freestyle wrestlers, as well as a powerlifter, strongman and author. Born in Estonia, he performed under the nickname ‘The Russian Lion’ and won a huge following for being both incredibly strong (he could supposedly lift a horse while still in his teens) and well spoken. He was fluent in seven languages, and his global popularity in the early 20th century helped popularise wrestling and weightlifting. Theodore Roosevelt is quoted as saying, "If I wasn't president of the United States, I would like to be George Hackenschmidt".

Being world famous and impressive to look at, Hackenschmidt was an ideal subject for the emerging technology of filmmaking. One of the first movies ever shown in NZ was of his fellow strongman, Eugen Sandow.

Early film audiences seem to have loved seeing muscular male bodies in action, which might have been related to the physical culture craze of the 19th and early 20th century. In 1910, Hackenschmidt toured Australia and New Zealand, with a troupe of other strongmen and vaudeville entertainers. Newspapers from the time, accessible via Papers Past, tell us that part of the show they put on during that 12-week tour included a film described in the Wairarapa Daily Times of 5 Februaryas “the world's wrestling championship between George Hackenschmidt and Joe Rogers, the twenty-one stone American champion.” Our Manager Film Preservation Dr Leslie Lewis believes that Hackenschmidt v. Rogers is it.

Film prints in those days tended to travel from one cinema to another, starting at their home studios in Europe or the United States and ending at the furthest point on a worldwide exhibition circuit. Being where we are, this was often New Zealand. At the end of its theatrical run, returning a used film to its home studio on the other side of the world was expensive. Distributors didn’t want to pay, so New Zealand cinemas would be instructed to destroy them.

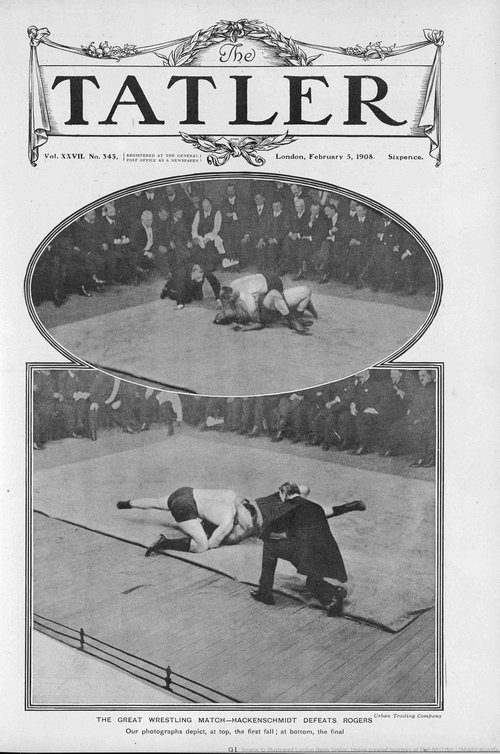

Page from Tatler, February 5, 1908

Proving that cinephiles have been around as long as cinema, sometimes people broke the rules and kept the films instead. When the silent era was over, these old films were rediscovered in all manner of places across New Zealand, including garden sheds, op shops, and in one case, buried under a macrocarpa tree. It’s because of these collectors that ‘lost’ overseas films have more than once been re-discovered in New Zealand. Between 2009 and 2013, in a joint project with the National Film Preservation Foundation, a large collection of early American films was repatriated to the United States by the New Zealand Film Archive, the organisation that later became part of Ngā Taonga.

It’s likely that this 35mm nitrate print of Hackenschmidt and Rogers took one of these paths to get to Ngā Taonga. By the early 1980s the single-reel film was in the collection of the National Library of New Zealand. Its provenance before that is unrecorded, but what matters most is that it was well cared for.

“The Hackenschmidt footage, along with many other early nitrate reels, both New Zealand and non-New Zealand, was deposited with the Archive by the National Library, who under various head librarians had the foresight to ensure our early film history was not lost by collecting and storing the films,” says Steve Russell, a long-serving member of the Archive’s staff.

Some of the early films in our care

Senior Preservation Archivist (Film Imaging and Sound) Richard Falkner describes how his team digitally preserved the 116-year-old film:

“The film was initially inspected carefully from end to end by our Senior Film Conservator Kurt Otzen, looking for damage, contamination and gauging the condition of the material. From here he carefully repaired damage to the film’s perforations and splices and cleaned as much as possible of the film’s surface to allow for the best possible scan.

Then the scanner operator digitised the film on our Arriscan XT film scanner, using an archival mode which transports the film as gently as possible. The film has shrunken over time, and you can see the beginnings of nitrate deterioration in the emulsion. All of these factors can make it very difficult for the scanner to transport the film, meaning the operator has to keep a close eye on it constantly for problems, such as the film creeping out of rack. At this point you have to stop the process, gently rewind the film, and start again. At times it is necessary to manually scan the film frame by frame. This can get a little tedious, but it’s all worth it when you see a finished result that hasn’t been seen for about a hundred years!

Once the whole film was scanned, it was carefully checked for any possible scanning problems or glitches, and then the resulting digital image sequence was loaded into HS-Art Diamant, our film restoration software. Here, the film was carefully stabilised, to remove any wobble introduced in the scanning, and then some slight restoration was applied to remove a little of the dirt and damage that has accumulated on the old print over time.

From there the digital sequence was exported, checked again, with the colour carefully corrected and the image cropped to emulate how it would have been originally seen.”

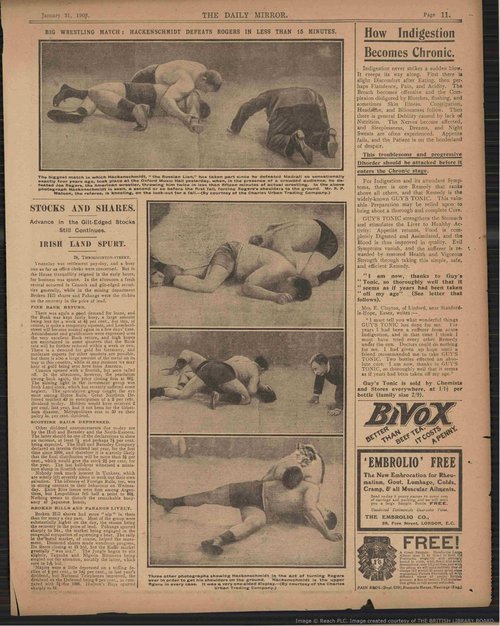

Page from Daily Mirror, January 31, 1908

Wrestling fans and scholars, who have waited years to see Hackenschmidt in action, were thrilled when the preservation was uploaded to our website on November 1. Sports blogs reported it under headings like ‘The Hackenschmidt Holy Grail’ and wrestling communities on Reddit have shared their appreciation. It’s also a rare treat for early film enthusiasts. At 1,310 feet it is an unusual length for a nonfiction film of the period and would once have been even longer: the exact title was once in question because the beginning and end of the reel are both gone. This is often the case because those were the first parts of a film to be damaged during projection and cut off. Lewis estimates that the original film, though advertised as 1,000 feet, was probably 1,500 feet long.

The Great Wrestling Match shows us what it really looked like when two great wrestlers of the early 1900s went toe to toe in front of an audience. It’s very different from the dramatised wrestling that most modern viewers are used to – this is a serious sporting contest, without gimmicks or flashy moves. The wrestlers’ costumes are simple and the ring spartan. The only advertisement to be seen is a board with the name of the production company, which was primarily there to ensure other production companies didn’t steal the footage and release it themselves - an early form of watermark. The audience are dressed in Edwardian suits and hats, all seated and watching attentively.

When they were first made, films like The Great Wrestling Match were seen as simple entertainment products with no historical value. Now these once-undervalued films offer a rare and precious window into the lifestyles and habits of the past. As Dr Lewis puts it, “Finally being able to make this film available to the public is not only a triumph of preservation but of conservation as well.”

Preserved by Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision.