By Virginia Callanan

The internal histories of different versions of the same story are as fascinating to archivists as the external histories of different prints. Together they provide us with the clues needed to uphold the film maker’s intentions. Ideally the version seen by initial audiences should coexist with, rather than be replaced by, a version seen by later audiences. Sadly, this was not the case with Rewi’s Last Stand / The Last Stand.

Timeline

1925 - Release of silent film Rewi’s Last Stand

1937 to 1939 - Rudall Hayward works on a new sound film Rewi’s Last Stand

1940 - New Zealand release of sound film Rewi’s Last Stand, 112 mins

1943 - Ramai te Miha marries Rudall Hayward

1946 - They depart to work in Britain

1949 - British release of The Last Stand, 63 mins

1954 to 1955 - The Last Stand theatrical release in New Zealand

1970 - The Last Stand screens on New Zealand television

The New Zealand Film Archive is indebted to thousands of individual depositors who have trusted their works into our care. Just prior to the Saving Frames film preservation funding we received a deposit, from an individual in Auckland, of nitrate film excerpts instantly identified as relating to Rewi’s Last Stand / The Last Stand. The feature itself had been selected for further picture and sound preservation to acknowledge the 150th anniversary of the 1864 Battle of Ōrākau, and with these new materials we had further impetus.

The deposit was 1,576 feet of 35mm nitrate sound print excerpts of variable condition (torn perforations, multiple splices, decomposition and water damage). Careful preservation onto safety stock and digital file allowed closer identification: twelve separate excerpts did not already appear on our existing version of the film. These have added new light on Hayward’s authorial intention for this historic story, as well as on his subsequent repurposing for an overseas audience.

Most of the excerpts were work-print with a dialogue and effects track but without the musical score – a clear indication that they would not have been incorporated into Rewi’s Last Stand, released in 1940. Other very similar takes would have been chosen instead. The significance of these new excerpts, however, is that they do show more of what Hayward actually shot and, subsequently, more of what he was forced to remove.

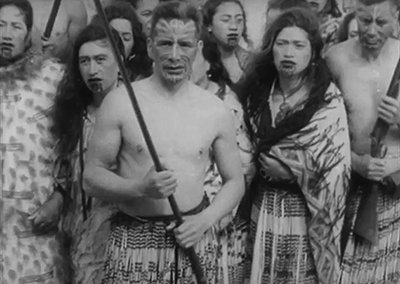

Hero image: Still from 1925 film, Rewi's Last Stand - Henare Toka (centre) as Tama Te Heu Heu.

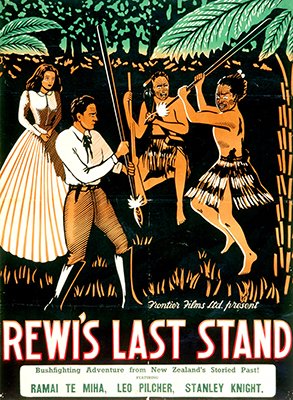

Film poster for 'Rewi’s Last Stand' (1940)

Our only surviving version is that known as The Last Stand, released in England in 1949. Here Hayward adapted his film for the British audience and distributors. Rudall and his partner Ramai set off for London in 1946 to break into the film business, taking a print and negative of Rewi’s Last Stand with them. Despite the film being technically out of date he felt “confident that the enthusiasm of the British public for outdoor pictures of the Empire [was] strong”¹. Understandably, nearly a decade after the story was filmed in New Zealand, it would need “to comply with a modern cutting tempo”² and be modified to suit “the English angle.” However, the 48 minutes that were removed, while tightening up the narrative and intending to recoup more money for investors, resulted in the permanent loss of so many original scenes from our film history.

We know that two waiata that Ramai originally sang were lost along with other performance sections. So it is fortunate that one of the newly found work-print excerpts is Ramai as Ariana singing “Papa Pounamu te Moana” to Rōpata in a romantic scene by the riverside. In another new scene she makes reference to a traditional chant, and also hurriedly mumbles a “charm” to ward off patupaiarehe. New passages in te reo Māori – for example Rewi Maniapoto instructing his defenders during a battle scene, along with explicit references to Christianity that are not in the existing version – provide significant information for film historians to engage anew with.

Just as James Cowan’s The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period (1922–23) helped Hayward recreate “an accurate representation of characters and events”³, so do Hayward’s own writings provide us with the basis to understand where our newly preserved scenes would have appeared in the original film. The Film Archive has a wealth of documentation relating to films, film makers and film-going in New Zealand. In Hayward’s case there are many papers, letters, photos, posters, interviews, and scripts that add rich contextual information to his film collection. For Rewi’s Last Stand we hold a “Scenario,” his original shooting script written in 1937. Another copy of this document is held at the State Library of New South Wales. Read in conjunction, with different annotations and missing pages, they offer a full picture of the original story.

James Cowan has had a resurgence of interest recently with the Borderland exhibition, and associated public talks, at the Turnbull Library Gallery during the commemorative period of the Battle of Ōrākau. The concept of cultural go-betweens has been applied to men like Cowan, Rudall Hayward, Alfred Hill, Henry Stowell, Charles Goldie, Johannes Andersen and others. What they all displayed was a political awareness of, and sensitivity towards, Māori history while at the same time romanticising the concept of “Maoriland” and the old pioneering frontier. Hayward himself was a product of late colonial culture and his work helps us explore the social shift from a colonial to national sensibility.

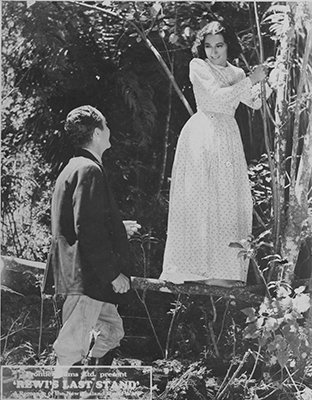

Ramai Te Miha as Ariana and Leo Pilcher as Robert Beaumont

Alfred Hill, composer and cultural go-between, began collecting Māori music in the 1890s. Their converging enthusiasm for “Maoriland” brought Hill and Hayward together on the production of Rewi’s Last Stand. Hill wrote an elaborate musical score, which unfortunately did not get the full rendering because of very limited facilities. It was recorded by Auckland’s 1YA radio technicians in the Avondale Town Hall, which operated as a cinema. The sound recording equipment was hooked up to a belt projector while Hill conducted the musicians.

Improvisation and invention have been the hallmarks of New Zealand’s pioneer film makers. Hayward often remarked that they “never had a feather to fly with” and his films were made on “half a shoestring.” In an interview from 1961 Hayward explains, “We had a sound camera which I built up with the help of friends who had lathes. Other parts I had made by Auckland companies, and I laboriously paid off the cost because no one was earning very much. We had a sound engineer, Jack Baxendale, a brilliant pioneering ham radio enthusiast, and he built not only the recording side but also the microphones. It was a major task for anyone to build condenser microphones in those days.”

“We developed the film in wooden tanks made from kauri boards two inches thick. The film was wound on wooden frames and 50 gallons of developer added. We had to rigidly maintain the temperature and the developing time to get a good result because the soundtrack was recorded alongside the film and the important thing was to get the correct density in the soundtrack, and this was extremely difficult.”⁴

Hayward had high hopes for the recut and re-record in Britain, “With the extended frequency range now available on recording equipment of the latest type in London, the music would be sensational.”⁵

As it turned out Hill’s musical score suffered in the recut, which itself did not live up to hopes of either dramatic sound improvement or ensuing commercial success for the original investment company Frontier Films Ltd.

However, the film remains a tribute to the enterprise and fortitude of its writer and director – Rudall Hayward.

Notes

- Correspondence, Rudall Hayward to Alfred Hill, 14 Dec 1946, Alfred Hill Papers, Mitchell Library, State University of NSW.

- Correspondence, Rudall Hayward to Alfred Hill, 5 Mar 1947, Alfred Hill Papers, Mitchell Library, State University of NSW.

- “Foreword,” Rewi’s Last Stand: A Scenario by R. Hayward, 1937

- Walter Harris (Supervisor National Film Library), interview with Rudall Hayward, 1961, NZFA Documentation Collection.

- Correspondence, Rudall Hayward to Alfred Hill, 8 Sept 1946, Alfred Hill Papers, Mitchell Library, State University of NSW.