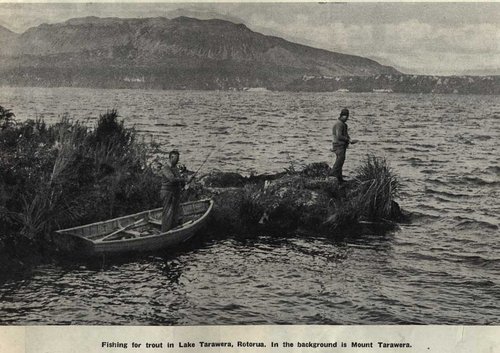

Above image: Fishing for trout in Lake Tarawera, Rotorua. In the backbround is Mount Tarawera. Courtesy Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19360610-53-3.

By Paora Sweeney

Working at the archives, one part of my role as an outreach advisor is to research and write about significant historical events in Aotearoa. Because I am Te Arawa, I thought to write something about the eruptions of Tarawera in 1886. However, while I was listening to some of the recordings, I came across interesting facts in relation to a particular tohunga from my iwi: Tūhoto Ariki.

The 10th of June 1886

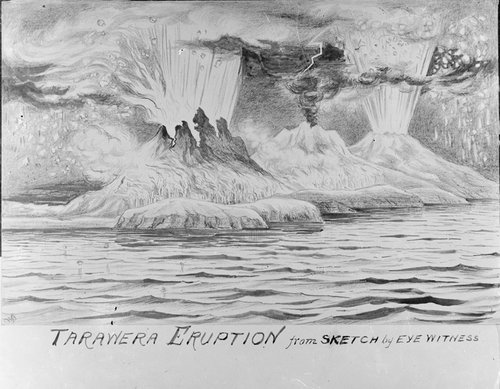

It’s been more than a century since the eruption of Mount Tarawera, the night the earth rattled sending massive boulders into the sky, painting the morning night sky a blazing red – which changed the face of the earth. It was 2am on 10th June 1886. Pakū mai ana te tangi, ka rū te whenua, ka ngaoko, ka ngunguru ka ngunguru, he ahi tipua kei runga, ka ara ake te paoa, ka pō, ka pō, ka awatea, first came the sound of an explosion, the ground began to shake, the land moved then rumbled, fire filled the sky, smoke descended, lasting on through the night onwards to the new dawn.’ Families from across Aotearoa were woken to shaking of the land, many had no understanding of what was happening and people recorded hearing the sound of an incredible bang.

A drawing depicting the eruption of Mount Tarawera

Courtesy Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 4-3658.

A life or death situation

Memories of these frightening events were captured in a 1975 episode of Spectrum

, the long-running RNZ documentary series. Appropriately called And There Was a Great Darkness, it shares readings of eye-witness accounts to the destruction.

Listening to this item and hearing those memories, I’m left feeling sorrow, and I wanted to learn more about what happened.

As a direct descendant of the Rangitihi iwi that lived near Tarawera, I was told many things about this horrific time and how it affected my ancestors. Many tīpuna did not survive, and I was told stories of my hapū being exiled and pushed out of our territorial boundaries by clouds of ash, as if it were a broom made of fire. My people were swept to the banks of the East Coast, eventually settling in the small beachside town known today as Matatā. Kei ngā mate huahua whakamene atu rā, koutou ki a koutou.

Te Wairoa Village that is no more

While listening in to this recording I realised that there were parts to the story I had not yet been told by my elders – the stories of the tohunga Tūhoto Ariki. Tūhoto Ariki was of Tūhourangi, who lived in Te Wairoa Village, a small township at the foot of Mount Tarawera. The village was set up by Christian missionaries to host guests and to provide tours of the Pink and White Terraces. Tourism became an important industry at Te Wairoa, and the township grew rapidly to include hotels and boarding houses. The township was later destroyed in the eruption, along with the Terraces which were regarded as the eighth wonder of the world.

Te Wairoa on the shore of Lake Tarawera before the eruption of Mount Tarawera

Courtesy Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 4-3691-40.

Tūhoto Ariki one of the last ancient tohunga

Tūhoto Ariki was one of the last ancient tohunga and was said to have lived up to a hundred years. Though each iwi have their own understanding of the role of a tohunga, most commonly tohunga were known to be chosen expert leaders in particular fields. Tohunga were known to be mediums connecting people to the spiritual realm and were also known to be ‘matakite’: a person that was able to forecast information about the future.

The Prediction and the Waka Wairua

Leading up to the eruption, Tūhoto Ariki had fears for the area and had predicted destruction. Prior to the eruption there was a sighting of a ‘Waka Wairua’ – a war canoe being paddled by rangatira Māori across Lake Tarawera that then vanished into thin air.

There are also accounts of others citing the waka. A tour guide named Sophia or Hinerangi recalls seeing a canoe in the distance being vigorously paddled, though not moving, and witnessing the transformation of those who paddled into dogs, before it disappeared. Tūhoto Ariki saw this as a tohu, a sign or omen that something terrible was about to occur in the area, and he uttered the words, ‘He tohu tēnei, arā kia horo tātau i tēnei takiwā – it is a sign, that we must flee this area.’ What was to come only confirmed his fears.

Following the eruption of 10 June, many blamed Tūhoto Ariki and believed that he was the cause. The village feared him and he was cast out. Returning to his house he was entombed by the eruption. However, four days after the disaster, rescuers dug him out of the ash and mud, and were surprised to find him still alive.

Tūhoto Ariki was taken to the Rotorua Sanitorium Hospital to be treated. On arrival the doctor washed him down and decided that he needed to have his hair cut. Tūhoto Ariki pleaded with the doctor not to do so, as the head is the most tapu part of the body, saying, ‘If you cut my hair I will die’. The doctor did not listen and broke the tapu. Although Tūhoto Ariki showed signs of recovery, he consequently died a short time later, as did the doctor.

It has been 135 years since the Tarawera eruption, and I’d like to pay homage to the many people who lost their lives, those that were caught in the ash, buried in the mud, those that lost their families, homes, the survivors that were displaced, the heritage that is lost, landscapes and dwellings destroyed. A moment in history never forgotten. Kei ngā mate huhua i riro tītapu, e mōteatea ana te ngākau, whakamene atu rā ki te pō whakahirahira, ki Hawaiki nui, ki Hawaiki roa, ki Hawaiki pāmamao.

You can hear more about Tūhoto Ariki and the history of the eruption in And There Was a Great Darkness . Tēnā, whakarongo mai.

The memory of Tūhoto Ariki lives on – he is remembered with the opening of the Tūhoto Ariki Trail in Rotorua that runs through the Whakarewarewa Forest.

Hei whakakapi

If you’re interested in researching your whakapapa, genealogy or history, I recommend you check out Ngā Taonga. I have no doubt you will be surprised with the stories you will uncover. For me, I’m excited to share the story of Tuhoto Ariki and I hope that his legacy will be passed down to the next generation.

Kei wareware i a tātou. Kei te rangatira, kei te tohunga, kei te matakite ahakoa ngā rau tau kua pahemo, ko koe tonu kei te poti o te ngutu, ko koe tonu kei te pua o mahara, he kura tangihia o te mātāmuri, e tau ana.

Nā Paora Sweeney