By Camilla Wheeler and Sarah Johnston (Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision)

In Gallipoli, food parcels from home must have been one of the few bright points in the Anzac soldier’s generally abysmal diet, which largely consisted of fatty, salty, tinned ‘bully beef’ and rock-hard ship’s biscuits.

New Zealand families and the Red Cross organised parcels containing tinned luxuries such as condensed milk, coffee and cocoa, as well as home-made biscuits and sweets. Most famous of course, is the Anzac biscuit, and with the centenary of the 1915 Gallipoli landings fast approaching, the debate over its origins seems set to rival the Great Pavlova Debate.

Food historians on both sides of the Tasman have been delving into vintage recipe books in a bid to see whether Australia or New Zealand can claim to be the originator of the rolled oat and golden syrup concoction.

(For the record, New Zealand is ahead in the race, with a cookbook published in 1919 featuring a recipe for ‘Anzac Crispies’, two years before Australia’s earliest entry in a 1921 cookbook.)

But whether it was baked first in a kitchen in Kerikeri or Coolangatta, the Anzac biscuit as we know it was most likely too fragile and perishable to last the long sea voyage to the distant Dardanelles. Instead, it is believed its name came from marketing-savvy home-bakers, who attached the name ‘Anzac’ to their oaty biscuits to promote sales at Red Cross fundraising stalls, sometime after the 1915 landings.

One home-baked treat which was actually enjoyed by soldiers in the trenches from Gallipoli to the Western Front, was the gingernut biscuit – and most likely it was baked to a recipe made famous by a Taranaki woman, Helena Marion Barnard, who received the British Empire Medal for her efforts.

Mrs. Barnard, originally from Nelson, was living in Eltham with her husband, daughter and eight sons when World War I broke out in August 1914. Six of her boys were to serve in that war, three of them on Gallipoli. Two of them were to die in the conflict, with the other four suffering illness, shell shock or serious wounds.

In this recorded interview made at the time of her 100th birthday in 1965, Mrs Barnard talks about how she first started making gingernut biscuits prior to the war, for her sons to take tramping, or ‘pioneering’, as she puts it.

Hero image: Selection of yummy Anzac Biscuits .

Interview with Helena Marion Barnard, 1965.

Helen Marion Barnard in April 1965, on her 100th birthday - with her surviving sons, Frank, Jim and Joe. (Photo courtesy of Winsome Griffin)

With the start of World War I, she again baked the long-lasting biscuits and packed them into tins to send to her sons and other soldiers overseas. Her biscuits were unusually small – about the size of a shilling, so the men could fit a handful in their pockets. She says she packed them into cocoa or golden syrup tins lined with newspapers, so the boys would have some reading material as well, while they ate.

Throughout the war, Mrs Barnard baked hundreds of pounds of the treats which were distributed to New Zealand and other Empire soldiers through the Red Cross. As well as baking, she knitted socks and balaclavas for the troops and raised money to buy an ambulance for the Army.

An article from the local newspaper in 1916, gives some insight into how the women of the Eltham district were raising money for the ambulance, and the sort of foods and other ‘comforts’ they were sending to their boys, including ‘Mrs H.J. Barnard 15 lbs home-made gingernuts, 4 pairs mittens.’

Article from the Hawera and Normanby Star, 17 August 1916. (Reproduced courtesy of Papers Past)

After the war, Mrs Barnard purchased a bell for Wellington’s National War Memorial Carillon, which was erected in Buckle Street in 1932. She had the bell named ‘Suvla Bay’ and dedicated it to her two lost boys.

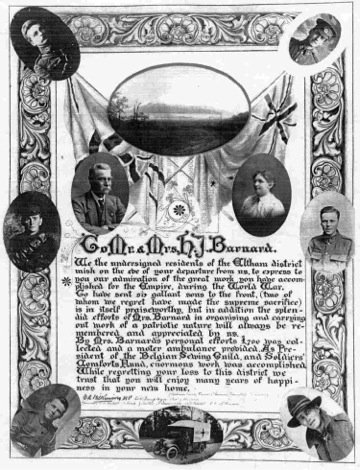

In recognition of their war-time fundraising and baking efforts, Mr and Mrs Barnard were presented with this beautifully illuminated scroll by the citizens of Eltham, when the family moved away from the district.

Mr and Mrs Barnard were presented with this beautifully illuminated scroll by the citizens of Eltham. (reproduced courtesy of Winsome Griffin)

It features photographs of Mr and Mrs Barnard in the centre, the ambulance at the bottom and her six sons who served in the war around the frame, including the two who were lost: Henry, at top right and Charles, bottom left.

When World War II started in 1939, 80-year-old Mrs Barnard was a widow, living in Island Bay in Wellington. With two sons as well as grandchildren now serving overseas, she once again tied on her apron. Food rationing meant it was hard for her to obtain the enormous quantities of butter and sugar needed. However, she managed to get a special permit from the Food Controller for extra rations and went on to make nearly a million gingernuts during the five years of this war, which she once again sent to New Zealand and other Allied troops overseas.

Mrs Barnard ended her baking career having made an astounding four and a half tons of gingernut biscuits in total. She was awarded the British Empire Medal and received thank-you letters from grateful servicemen and their mothers, all over the world. The letters found their way to her often simply addressed to ‘Mrs Barnard, The Gingernut Maker, Wellington, New Zealand.’

One which was published in the local newspaper, contained the thanks of a WWII midshipman, Peter S. Burns of the Merchant Navy: ‘…allow me to assure you when I am freezing to death standing on the bridge… in the middle of the Atlantic and whenever my hand goes frantically into my coat pocket to get a gingernut, my thoughts go to the kind person from whom I received them.’

As you hear in the interview, Mrs Barnard was fond of sharing her recipe. Throughout both wars, she built up a correspondence with other soldiers’ mothers, sharing the recipe and samples of her biscuits. In the spirit of this, Ngā Taonga cataloguer Camilla Wheeler and client supply archivist Sarah Johnston have been baking Mrs Barnard’s recipe. Camilla converted the large quantities into proportions more manageable for modern bakers (the original recipe calls for 2 ¼ pounds of flour and 2 pounds of golden syrup!) and they have experimented with different methods and baking times.

Archive staff have been taste-testing the results over the past few weeks and are happy to report the 100-year old recipe withstood conversion very well, producing a very tasty, dense, chewy biscuit which keeps well and is perfect for dunking in a cup of tea.

You can read both Mrs Barnard’s original recipe and our modern conversions here.

Thank you to Barnard family researchers Winsome Griffin, Christine Clement and Louise Mercuri for permission to reproduce material from their website .