These films include some of the very oldest ever made, and many of them are in remarkably good condition. We find out more about the process and speak to some of those involved.

Nitrate film has an unfair reputation of being dangerous. As a ‘flammable solid’, under extreme circumstances it can spontaneously combust – and is incredibly difficult to extinguish. This is due to the film being made of nitrocellulose, an early form of plastic that can naturally decay over time. Nitrate was used from 1896 until the early 1950s and captured early, precious cinema recordings.

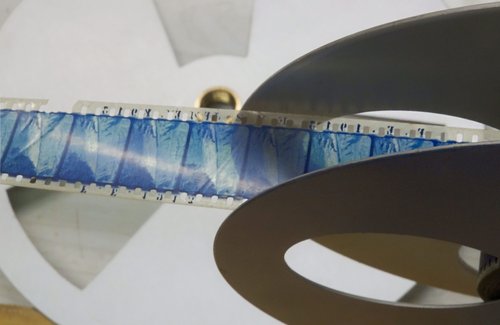

Winding a film onto a new reel

The risks with nitrate can be greatly reduced through careful monitoring and handling, storage in a safe and stable environment, and a periodic ‘wind through’ of the film. Ngā Taonga staff undertake this winding process every year and it serves two main purposes. Winding film onto a new reel brings it out of its tin where it has been wound up and provides an opportunity for the release of gases that may have been given off by the film. This off-gassing process is an early sign of degradation.

Secondly, it gives staff an invaluable opportunity to check the condition of the film. Each film is assessed and priorities are made for further preservation and digitisation.

Winding through ‘The World’s First Lady Mayor’

The wind through is a methodical and repetitive task; it’s also very social and a great time to get ‘hands on’ with archival material. Staff are rostered on in groups of four to work through the material and all senses are engaged: they visually inspect the film, feel how it behaves as it winds, and listen for any stickiness as the film moves. It’s a large operation with around 4,100 reels of film to work through, totalling over two million feet1, and more than 900 hours of very old footage.

‘I loved it!’ exclaims Emma Richardson, Collections Manager. ‘Being hands on with the material really reminds you of why we do what we do.’ Richardson spent three days on the wind through and really appreciated getting to see some of the film material she was familiar with from digital versions, particularly footage from World War One and The World’s First Lady Mayor. Digital copies can whizz around online but they are taken from scans of decades-old film material, which is kept safely in a vault. ‘It feels like a hidden, magical part of the organisation.’

Staff visually inspect every piece of film during wind through

The oldest pieces of nitrate in our collection are 125 years old – Georges Méliès’ Cortège du Tzar allant à Versailles and Le Manoir Du Diable from 1896. Expert care is essential to make sure they don’t degrade – this is a natural process with nitrate film, which was once thought to be inevitable. When nitrate begins to degrade, the cellulose layer goes from a pliable plastic to being both sticky and brittle (though still windable on non-mechanised winders, as seen in the pictures), to a crystalline mass, to a red powder. Left unattended – in a shed or an attic for decades – opening a can of film may reveal a jumble of shattered, crumbling fragments. The then-director of the New Zealand Film Archive described this in the Archive’s newsletter in 1982: ‘Whatever the conditions of storage all nitrate sooner or later comes to an unstable, festering, sticky end.’ But that’s no longer the case.

Dr Leslie Lewis, our Film Preservation Manager, notes, ‘It was once thought that nitrate film was on the verge of degrading away, but archivists globally have learned that with proper care, nitrate can last longer and in a better condition than its replacements – particularly ‘safety’ film which has an acetate base.’

Looking good!

Our nitrate film is kept in a special vault that keeps constant temperature and relative humidity and also has safety precautions in place to prevent fire. These safeguards include non-spark (‘explosion proof’) lighting and no power outlets. Mobile phones are also banned. The specially-designed vault is inspected and re-certified each year to ensure that it remains fit-for-purpose.

It is extremely pleasing to report that the Ngā Taonga collection is in good shape as it has been closely monitored over the last 40 years. ‘Every year we do find a bit of film that needs to be disposed of, but it is less and less every time,’ explains Dr Lewis. ‘We’re most likely to find decomposition in new deposits where the film has been stored by someone in their basement or attic or under their bed for decades before being deposited with Ngā Taonga.’

Films are returned to their cans and re-shelved

‘Every year we do find a bit of film that needs to be disposed of, but it is less and less every time’

If the degradation is too advanced, there may be no choice but to dispose of parts of the film. Where this occurs, the affected footage is carefully cut out. At the end of the wind through, the army comes and picks up the damaged film and destroys it. This is critical work and is a requirement of safe storage of nitrate film as prescribed by FIAF, the International Federation of Film Archives – of which Ngā Taonga is a member.

The wind through this year was a success, with only a small amount of film material needing to be removed. Complete for another round, the films are returned to their cans, where they’ll sit safely till next year.

How films are stored in our nitrate vault

1 ‘Feet’ is the standard measure for film length, and relatedly, runtime or duration.

Read more about nitrate conservation and projection