Homeschooling was the reality in New Zealand 72 years ago, when schools stayed shut after the summer holidays and didn’t reopen until after Easter. In Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision’s regular segment with RNZ’s Jesse Mulligan in April, Sarah Johnston shared some recordings of memories of that time, when it was a polio epidemic that was keeping New Zealand children at home and indoors.

Poliomyelitis or infantile paralysis, as it was also known, was a terrifying disease which broke out multiple times in New Zealand between 1919 and the early 1960s, when the epidemics were finally eradicated by vaccines. Hundreds of people died but contracting polio could also mean a lifetime of disability – even if you survived. The muscles in patient’s limbs wasted, leaving them crippled. In many cases, muscles which controlled breathing were also affected, meaning patients could require months or years of treatment in an ‘iron lung’ – a machine which mechanically stimulated the chest muscles to help them breathe.

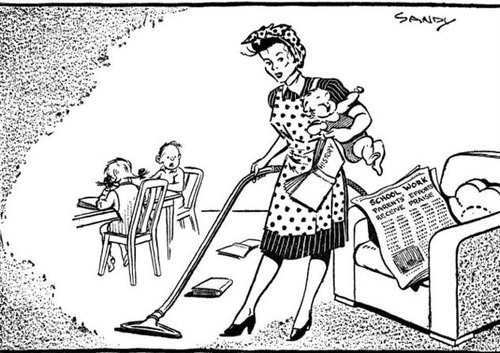

Hero image: 1940s Cartoon of a mother cleaning and homeschooling her kids.

Nurse with child in an iron lung machine. (Mayor John F. Collins records - Collection #0244.001, City of Boston Archives)

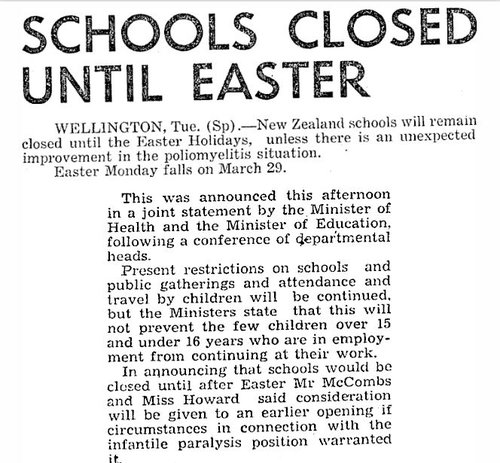

In late 1947, a new polio epidemic broke out and New Zealand schools wound up for the year early. Children were banned from public transport or anywhere crowds might gather during summer, such as cinemas, campgrounds or milk bars. In late January, Minister of Education Terence McCombs made a public address by radio, telling the country that the 1948 school year would not be restarting until after Easter (in March). Instead, he announced, homes would become ‘miniature schools’. He noted ‘that this must affect the normal routine in most households, will be obvious to everyone… but the health of our children must be the first consideration.’ (Hon. Terence McCombs in 1948 in Retrospect).

In 1993, Radio New Zealand’s long-running Spectrum programme made a documentary looking back at this long, hot, frightening summer. Around the same time, The Correspondence School made its own radio programme, looking back on its role in supplying remote learning to the nation’s school children in 1948.

Newspaper headline announcing school closures. (Northern Advocate, 27 Jan 1948 - courtesy Papers Past)

In a pre-internet era, the Correspondence School used to regularly broadcast a short lesson on the radio, for students who lived in remote areas. This amounted to about 40 lessons per month. Once the country’s entire school roll became confined to home by the polio epidemic, the Correspondence School had to step up to provide 40 radio classes every week.

Past students and teachers recall how the lessons were sent out in green canvas envelopes, to be completed and returned to local schools, where teachers sat in empty classrooms to mark them.

Because polio affected children more than adults, the entire population was not in ‘lock-down’, although children were confined to home and all public gatherings were cancelled. Families who were unlucky enough to have a child contract polio however faced the added stress of quarantine.

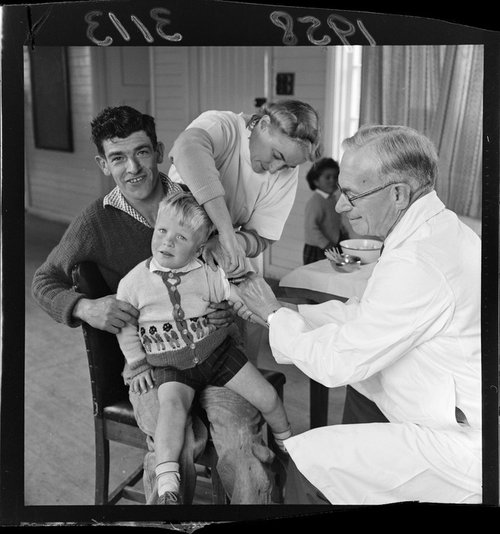

Dorothy Ford’s six year old daughter was hospitalised with polio, leaving her stranded at home in the construction village at Karapiro, with two younger children. In the Spectrum documentary she recalls how her grocery order had to be shouted from her front porch to the local store keeper, who then dropped her supplies over the fence. When the Salk polio vaccine arrived in New Zealand in 1956, she says she rushed to have her other children vaccinated. Thanks to the near universal uptake of the vaccine, the dreaded epidemics were eliminated in New Zealand by the early 1960s, and Dorothy and others affected by the disease told Spectrum they hoped it would never again be allowed to re-occur.

Titahi Bay boy receiving the polio vaccine, 1958. (Evening Post newspaper - courtesy Alexander Turnbull Library Ref. EP/1958/3113-F)