By sound history researcher Sarah Johnston

Some of the first recordings sent back to New Zealand for radio broadcasts in late 1940 provide some insight into life on board the troop ship on which the Broadcasting Unit was travelling, as part of the Third Echelon of the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

The ship was the Empress of Japan, a luxury Trans-Pacific passenger liner belonging to the Canadian-Pacific company, but requisitioned for war work in late 1939. She was only 10 years old, with what was described as ‘an extremely impressive interior – lofty public rooms decorated and furnished with extensive use of natural wood. The main lounge, two decks high, had a large oval domed ceiling and a musicians’ gallery. A Palm Court and ballroom extended across the whole 83 feet width of the ship at the forward end of the promenade deck.’ (1)

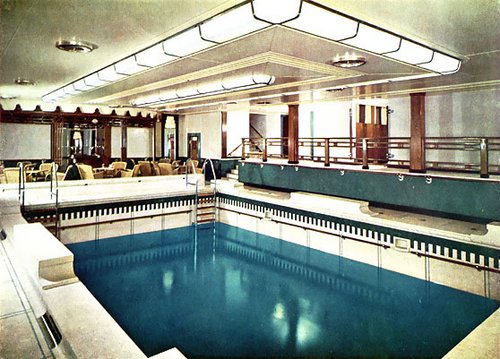

Although many of her luxury fittings would have been stripped out for war service, some still remained and New Zealand officers enjoyed the privilege of being able to swim in the ship’s rather magnificent tiled, indoor swimming pool (A canvas pool was set up on deck for the enlisted men).

The tiled swimming pool on board the troopship, the former Empress of Japan. Courtesy Empress of Scotland: an illustrated history

The Broadcasting Unit staff had honorary military ranks and the privileges of officers, even though they were still employed by the National Broadcasting Service. (They would later come under the control of the 2NZEF Public Relations Office, but that was not fully set up until May 1941.) (2) As officers, they enjoyed better quarters on board, with cabin service provided one of the Canadian-Pacific line’s Chinese stewards.

In September 1940, soon after sailing from Wellington, “Johnny” Johnston, the Broadcasting Unit’s 23-year-old assistant engineer, wrote to his parents about his very civilised introduction to military life: ‘We are being wonderfully looked after on this ship… At 7am Ah Chow our cabin steward comes in with a cup of tea and asks if he can run our bath. Breakfast is at 8.30am, starting off with prunes or figs, then poached mullet, half a dozen sorts of omelet and rolls and coffee… All the servants are Chinese and the soul of perfection. When you walk into mess, one is always ready to pull your chair out and pour your iced water.’

Sunday, 8 September 1940. ‘We are now in the tropics and it seems to get hotter every day. Yesterday they opened the swimming baths. There is one aft for the men and we [the officers] use the ship’s permanent one which is extremely good. It is all tiled and about 30 feet long and 15 feet wide. You can just imagine what a boon it is being able to have a swim after sweating like a pig in the [recording] truck.’ (3)

The Broadcasting Unit’s recording truck was travelling with them, with microphone cables running from the hold up onto the deck, to enable recordings. After making their initial discs from the Wellington wharf-side as the Echelon prepared to embark, the Unit’s staff continued testing their new equipment by making recordings of the crew and fellow passengers. Few of the New Zealand men had a lot to say at this point – their war experience being only a few weeks old. The Broadcasting Unit had better luck with the seasoned crew of the Empress of Japan finding some radio ‘talent’ in the form of the ship’s First Officer L.M. Goddard who recalls his colourful sailing career which began at the age of 13, in the late 19th century. The ship’s Scots boatswain, Bosun Wilson, also seems a natural at the microphone. In a ‘radio talk’ he details his life story, which included serving in Canada’s Royal North-West Mounted Police in the Yukon Territory. At the start of World War I he was working as a gold miner and walked 360 miles through the Yukon to join up, serving with a Western Scottish Regiment.

A few days after making this recording, the broadcasters again handed Bosun Wilson the microphone, allowing him to commentate as the New Zealand men took part in one of the maritime world’s oldest ceremonies, “Crossing the Line”. This is a centuries-old naval tradition that marks the first time a person sails across the Equator. Bosun Wilson and Doug Laurenson of the Broadcasting Unit recorded a commentary on deck describing the good-natured hi-jinks, which involve the ship’s crew dressing up and taking the roles of various members of ‘King Neptune’s Court’. Neptune’s ‘Bears’ cover the ‘land-lubber’ initiates (who are Crossing the Line for the first time) with flour-paste lather, pretend to shave them, and end by dunking them in the swimming pool. An old hand at the ceremony, Bosun Wilson wryly evaluates the performances of the New Zealanders taking part.

Broadcasting engineer “Johnny” Johnston wrote home to his parents about making the recordings, and wondered if the Unit was making history, being perhaps the first to record the ancient ceremony? ‘Everything was done with great formality, all the characters were in costume…and the commentary by the Bosun was quite good. The entire ship’s crew were delighted when we played the records back to them, so much that we had to leave a copy of the discs with them.’ (4) The Officer Commanding the troops on board, Colonel Clayden Shuttleworth (24 Auckland Battalion), was able to provide a certificate showing he had already Crossed the Line, so he is spared and Captain Jack Redpath of Christchurch becomes the first officer ‘victim’ instead.

Crossing the Line on the troop transport Empress of Australia, August 1941. The initiate being ducked by the ‘bears’ after being shaved by King Neptune’s barber. Imperial War Museum A5176 via http://hmsgambia.org/

Two nurses and several men of the 14th and 15th New Zealand Forestry Company also receive a dunking, but as the ship was travelling through the steamy tropics, it was probably a welcome dip – and a diversion from boredom, which was an issue for many men on board.

The staff of the Broadcasting Unit may have enjoyed the novelty of being treated as officers with tea delivered to their cabin, but the official war history of one of the Army units on board, 24 Auckland Battalion, describes a less-pleasant voyage for enlisted men, who slept in hammocks in cramped conditions: ‘The [ship] carried a total of 2,635 men. Accommodation provided for no more than 2,250 and the ship was considerably overcrowded… As for training, the chronic shortage of equipment was still in evidence, but now among the other things lacking was space for movement… military activity assumed two forms, one consisting of lectures and the other of physical training and route marches round and round the promenade deck. As for amusement, concerts were arranged, films were shown… but sports and deck games were limited by the cramped conditions.’ (5)

Additionally, the men on board suffered through several outbreaks of disease, including measles, which struck Noel Palmer, the Broadcasting Unit’s officer-in-charge.

The Unit tried to alleviate some of the boredom, playing recorded music through the ship’s loud-speaker system for the men: martial tunes to accompany the daily route marches around the deck, but as Johnny Johnston wrote, ‘The universal favourites with the men are George Formby and Gracie Fields. I’m sure they would be quite content if we played no others at all.’ (6) The Unit also recorded two ship’s concerts organised by the men. This concert featured two numbers by tenor Tony Rex. Already an established performer in Auckland, within a month of arriving in Egypt in October 1940, he would become a founding member of the famous Kiwi Concert Party, which entertained the New Zealand Division throughout the rest of the war. (7)

Tony Rex and one of the Kiwi Concert Party female impersonators, performing in Maadi, Egypt, 1941. Ref: DA-01442-F, Alexander Turnbull Library.

Rex sings two popular numbers, “If I were King” and “On the Road to Mandalay”, which would have been familiar to the men. More novel, is another number, written on board and performed byDr Jock Caughey of Auckland.

Portrait of Dr. John Egerton Caughey, taken by Clifton Firth, 7 June 1939. Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 34-C28A [via Online Cenotaph]

Major Caughey would eventually become Commanding Officer of No. 3 New Zealand General Hospital during the war. He was mentioned in dispatches and after the war, and became New Zealand’s leading neurologist and Dean of Otago Medical School. (8)

In September 1940 however, he was on board an over-crowded troop ship, singing a doggerel soldier’s song with lyrics penned by the on-board army medical staff. The title is not given, but the refrain, which the audience also sings, repeats, “A soldier leads mostly a dog’s life.” It is a humorous litany of complaints about the voyage and life on the troop ship, including the hot weather, the outbreak of measles, the dunkings by ‘King Neptune’ and even the painful vaccinations inflicted on the men by Caughey’s own unit. There is good-natured ribbing of the nurses and fellow officers, but Colonel Shuttleworth, the ship’s CO, again escapes, this time thanks to his surname:

‘One Shuttleworth here, is the Colonel. Of course, he should be in this song. But I can’t find a rhyme for his name dear, I guess that it’s just too, too long!’

References

- Sharp, P..J. The Empress of Scotland: an illustrated history [online] https://www.angelfire.com/pe2/pjs1/index.html

2. Oosterman, A. ‘The silence of the Sphinx’: the delay in organising media coverage of World War II, Pacific Journalism Review 20 (2) 2014. [online] https://ojs.aut.ac.nz/pacific-journalism-review/article/view/173/136

3. Johnston, Norman Balfour. Personal correspondence, “At sea”, 06 September 1940

4. Johnston, Norman Balfour. Personal correspondence, “At sea”, 14 September 1940

5. Burdon, R.M. 24 Battalion p. 7. Part of: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945. Historical Publications Branch, 1953, Wellington [online] https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2-24Ba-c1.html

6. Johnston, Norman Balfour. Personal correspondence, “At sea” 23 September 1940.

7. Ward, Aleisha. Musicians at war: The Kiwi Concert Party of World War II, [online] https://www.audioculture.co.nz/articles/musicians-at-war-the-kiwi-concert-party-in-world-war-ii

8. McDonald, W.I. Inspiring Physicians: John Egerton Caughey. The Royal College of Physicians [online] https://history.rcplondon.ac.uk/inspiring-physicians/john-egerton-caughey

About the author

Sarah Johnston is a former broadcaster and sound archivist, researching recordings made by the New Zealand mobile broadcasting units during World War II. You can read more about the project on her blog World War Voices.