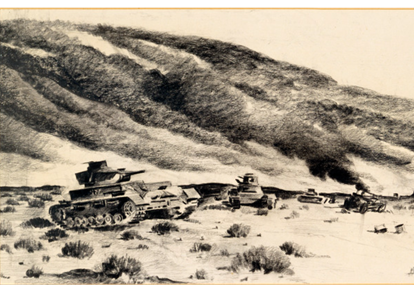

Above image: Battlefield at Sidi Rezegh, November/December 1941 Artist: Peter McIntyre (R122497098 Archives New Zealand)

By Sarah Johnston

Among the recordings made by the National Broadcasting Service mobile recording unit in North Africa during World War II is a series of discs in which a soldier tells the story of a New Zealand Divisional Cavalry gun operator, who was wounded in a tank battle in Libya in 1941. (The discs were sent back to New Zealand for radio broadcasts by the NBS, a forerunner of RNZ, and are now held in the RNZ Sound Archives collection at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision).

The story is that of a soldier who goes by the nickname ‘Sparks’ and the speaker who tells it is Corporal Robert Loughnan. Loughnan was a former Canterbury high country shepherd, now a gunner with the ‘Div. Cav.’ and the story he tells is, in fact, autobiographical. The gunner, who he named ‘Sparks’ in his story, was in fact Loughnan himself, and the story is of what he endured during and after the battle of Sidi Rezegh in Libya in late November 1941.

The story which Robert (Bobbie) Loughnan recorded in Egypt has been digitised and can be listened to in two parts in Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision’s online collection. Part 1 covers the battle and how he was wounded when his tank was hit by German fire. Part 2 tells how, around a week later, he survived the sinking of the ship S.S. Chakdina, which was torpedoed and sank while carrying wounded men from Tobruk to Alexandria. Together, they form an powerful first-person account of two important moments in the history of the New Zealand Division during the North African campaign of World War II.

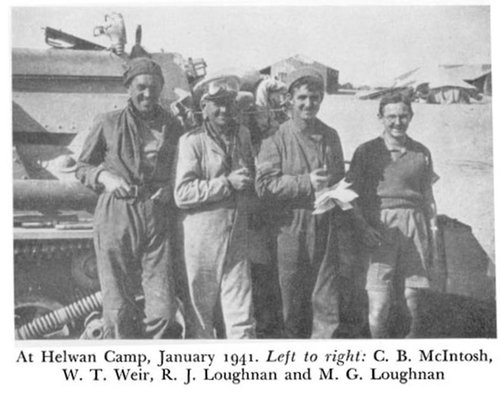

Photograph of Div. Cav. members from Bobbie Loughnan’s own collection (he is second from the right). Published in the Official War History of the Divisional Cavalry, 1963, by R.J. M. Loughnan (via the New Zealand Electronic Text collection).

The story was written by Bobbie as his entry in a short story competition run by the 2NZEF Archives in 1942, asking members to send in a written ‘eye witness account’. Loughnan called his tale ‘A Simple Country Lad’, reclaiming the dismissive phrase Hitler had used when he referred to New Zealand’s forces as ‘poor, deluded, country lads.’ The phrase was also co-opted by the National Film Unit in this 1941 film-reel about New Zealand men training for war.

Bobbie had a talent for writing and he tells a gripping tale of the intensity of a tank battle, in which he was wounded badly in both hands and transferred to an overcrowded hospital in Tobruk. A few days later he was taken on board the converted cargo vessel Chakdina, which was carrying 400 Allied men to other hospitals in Egypt, plus 120 crew and 100 German and Italian prisoners of war. However, it was torpedoed by an enemy plane at around 9pm on 5th December 1941, and sank rapidly with the loss of 400 lives, including 80 New Zealand wounded. Thanks to the efforts of a fellow Div. Cav. member Morven Stewart, Bobbie survived the sinking and he describes floating in the Mediterranean for several hours before being rescued under fire by the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Farndale. Unable to use his wounded hands, he clung with his teeth and toes to a cargo net on the side of the ship, until he was able to be pulled aboard.

For me, it stands out as one of the few accounts of the war recorded by the mobile broadcasting unit, in which a man speaks openly of his emotions and mental state during combat and at times of great stress. During a period when many New Zealanders, particularly men, publicly maintained a ‘stiff upper lip’ about the hardship of war, Bobbie’s story seems almost modern in his description of enduring what we would now call a panic attack and post-traumatic stress.

It certainly stood out to broadcaster Noel Palmer, who recorded it on discs at Maadi Camp in September 1942. Palmer wrote to the Director of the National Broadcasting Service, James Shelley, in a letter that accompanied the discs back to New Zealand, saying: “It is, I think, quite the most outstanding “Personal Experience” we have yet recorded (1).” Army archivist Captain E. Halstead agreed, writing to his counterparts in Wellington that the story was “excellent” and recommending it should be published in booklet form as an official Army publication (2). (It is unclear if this ever actually happened – so far I have not found any trace of such a publication).

When it was recorded in 1942, the title ‘A Simple Country Lad’ was hand-written (probably by Noel Palmer) on the disc labels. The story would have played on air in New Zealand sometime in late 1942, in one of several radio programmes dedicated to recordings sent back from the war fronts by the mobile broadcasting units. However, when the discs came to be catalogued by the RNZ Sound Archives several decades later, the connection to Bobbie’s story and the context of the title was no longer known. Cataloguers possibly felt the title seemed a little dismissive, and so listed the recordings with a title more descriptive of the contents: ‘The story of a gunner injured in Libya.’

And so they remained until February this year when Bobbie’s son Robert contacted me via my blog mentioning his father had recorded a story entitled ‘A Simple Country Lad.’ The name rang a bell as I had come across the correspondence from Noel Palmer and Captain E. Halstead in my research at Archives New Zealand. A quick search on his father’s name in Ngā Taonga’s catalogue found the recordings – albeit, under the later title ‘The story of a gunner injured in Libya.’

Robert Loughnan very kindly shared with me the journey he has been on uncovering the details of his father’s wartime experience and recovery, and with his permission, I can share some of those details here. After recovering from his wounds, Bobbie Loughnan was eventually furloughed back to New Zealand in 1944. He married, raised a family and worked as a stock buyer and then as public relations officer for the Canterbury Frozen Meat Company. He had some involvement with rural radio programmes in this role, on station 3YA in Christchurch. Additionally, as publicity officer for the Canterbury Ski Association he used to present weekly snow and ski reports on air during winter months. Bobbie passed away following a series of strokes in 1984, and some months later, his son Robert visited the Radio New Zealand Sound Archives (which were then in Timaru), hoping to be able to hear some of these reports if they had been archived. To his great surprise, he heard instead, the recording his father made in 1942 – a very emotional experience as Bobbie had never shared the details of his wartime wounding and shipwreck escape with his family.

This prompted a long period of research by Robert into his father’s war and he was able to meet Morven Stewart, the fellow New Zealand Div. Cav. member who Bobbie mentions in the recording and who was responsible for him surviving the sinking of the Chakdina.

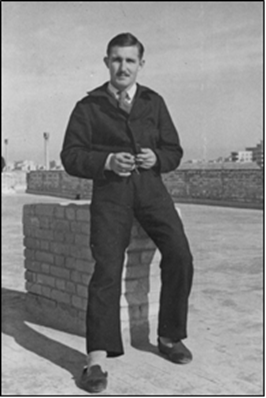

Robert also eventually met former New Zealand army nurse Gaye Collington, who had nursed Bobbie in Egypt. It was she who had encouraged him to write down his experiences as a way of processing the trauma he had gone through. It was Gaye who took this photo of Bobbie Loughnan, in his ‘hospital blues’ (patient’s uniform) on the roof of the Egypt hospital in 1942. She talked about her experience nursing Bobbie in an oral history, which was published in the book ‘Mates and Mayhem’ by Lawrence Watt (HarperCollins, 1996).

Bobbie Loughnan in his ‘hospital blues’, Egypt, 1942. [Courtesy Robert Loughnan]

Incredibly, Robert also met a former British seaman Les Edwards, who was the Royal Navy sailor who had pulled the wounded Bobbie out of the Mediterranean and aboard the HMS Farndale. Les had eventually settled in New Zealand and advertised through the R.S.A. Review newspaper that he wanted to meet any survivors of the Chakdina sinking. Morven Stewart saw the notice and eventually Robert Loughnan was able to meet up with Les and Morven in 1999. As he wrote, “How do you say thank you in some adequate manner to the very men who in rescuing my father, gave me life?… What a lucky man I am to have met, and known, Gaye, Morven and Les. All three in some way responsible for the life I have enjoyed.” (3)

Morven Stewart, Robert Loughnan, Les Edwards in 1999 [Courtesy Robert Loughnan]

Robert also kindly shared with me a letter his father Bobbie wrote to his parents during the war, telling them about the story and how he came to record it.

“I read in the NZEF Times of a competition instituted by the Official Archivist for personal account stories of the Div, fighting. The Archivist, one of the Public Relation Blokes, was looking for material of a more personal nature than the bald statements of fact which come to him in each Unit’s War Diary. He required this stuff to use in the eventual writing of the Division’s History after the war… I wrote and wrote and wrote and found myself getting really excited over it all. And for two nights I wrote away there till the small hours. When it was done I borrowed a typewriter and typed a draft. 20,000 words it was and some effort for me to type. Then I got busy with a blue pencil and gave it an awful hiding. Finally produced the finished article… I handed the manuscript to Murray, to pass in, as we went through Cairo and up the line. I was thankful to see the last of it – so I thought.

A week or so later I had a message from Murray saying that my story had been lodged all right and had produced a visit to him in Base by another Public Relations bloke – the wireless recorder – to find out whom this Loughnan bloke was and whether he would make a recording for broadcast.

In September the Div was given four days Cairo leave before the big fight, so I went out to Maadi expecting to be introduced to a microphone and with a commentator, to make this sort of record:

Commentator: “What’s it like in battle?”

Me: (nervously) “Pretty bloody”

C: “What’s it like when the Stukas come?”

Me: “Pretty bloody”

C: “Do you like fighting?”

Me: “Not bloody likely”

…….etc. etc, ad lib.

But I was greeted instead by my whole manuscript all jacked up for easy reading and ready annotated for emphasis and inflexion etc. with every page (there were some twenty of them) stamped by every censor imaginable. There was the Chief Naval censors stamp, RAF Middle East, GHQ Middle East and Lord knows what.

I was coached up in reading. We had a trial run for a page or so and finally got to work. The whole business burnt up the best part of a day. In one place I broke down (did my scone) and the recording wallah took the record, 12 inches of it, broke it over his knees and just said “OK, take a spell and then go back to so-and-so.” Oh yes. They turned your son into quite a showman.

Then, when it was all over, I got the biggest kick of the lot. He played it all back to me and made me follow very critically right through. While this was going on the door opened and in came someone in a, then, strange uniform. The recorder turned down the volume for a minute and introduced me to this bloke. As usual I played no attention to his name but shook his hands, sat down and went on listening. After the last record – there were some 16, 12” sides – this fellow said: “Did you make that recording?” The recorder pipes up: “Yes, and wrote it. He happens to be the hero too.”

In the broadest of accents comes the spontaneous remark: “Boy, you’ve a natural commentator’s voice” (pronounced – commentah). He was a technician from one of the big American Commercial Radio Links!! That was the biggest “kick” of the lot.” (4)

Bobbie Loughnan’s skill with words continued after the war. As well as his publicity work on radio, he was tasked with writing the official war history of his unit, the New Zealand Divisional Cavalry. It was published in 1963 and can be read online.

(Many thanks to Robert Loughnan for his help in writing this story of his father’s recording and permission to republish photographs and excerpts from his correspondence).

Footnotes:

- Noel Palmer to James Shelley, National Broadcasting Service, 17 Sep 1942. Archives NZ R22011495

- Captain E. Halstead to E. McCormick, Army Archives, HQ Wellington, 18 Sep 1942. Archives NZ R22011495

- Robert Loughnan, The sinking of the Chakdina, March 2022.

- Personal correspondence, R.J.M. Loughnan to his mother, 21 September 1943.

About the author: Sarah Johnston is a former broadcaster and sound archivist, researching recordings made by the New Zealand mobile broadcasting units during World War II. You can read more about the project on her blog World War Voices.