By David Klein

There was a whiteboard covered in text and Post-Its, like something out of a detective movie. A group of people spent months discussing possibilities – what was in and what would get cut? The topic: the curation and development of a video compilation that would become Ngā Wai e Rua: Stories of Us – a 45-minute programme looking at the dual heritage of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Watch Ngā Wai e Rua: Stories of Us

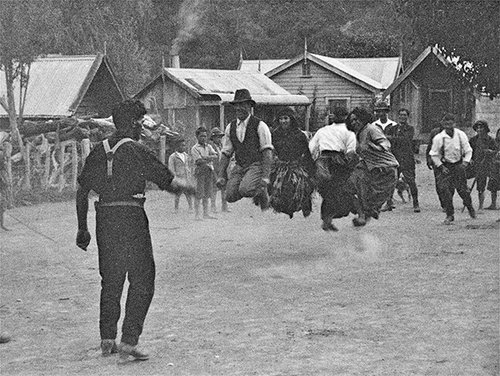

‘We drew on a lot of expertise from across the organisation to compile footage’ explains one of the programme curators, Lawrence Wharerau. ‘There was some obvious stuff that always had to make the cut – footage from 1901 was essential’. These kinds of ideas went up on the whiteboard as a key part of the curatorial process. The team would review the brief, take a look at what was available, ask what worked best and took another step closer to the finished product.

Hero image: The waka Te Aurere at sea.

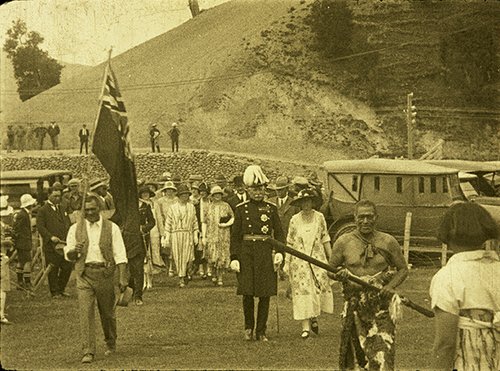

Still from Māori Hui at Tikitiki - Governor General Sir Charles Ferguson and entourage are welcomed onto Te Rāhui Marae, Tikitiki, for the consecration of St Mary’s Church on 16 February 1926.

The programme was developed with the Ministry of Education (MOE) as a response to Tuia250, with a view to reflect visually ‘dual heritage and nationhood’, and the building of a nation. It had to capture 120 years of recorded encounters, drawn only from filmed and archived records, and be contained to an hour. ‘It was a big ask!’ recalls Diane McAllen, one of the other key curators. ‘We had a range of limitations and it was a resource- and time-heavy project’.

Alongside McAllen and Wharerau in the curatorial team was Di Pivac, who has since left the Archive. The three of them had plenty of healthy debate and involved many additional opinions from other colleagues. ‘It really was a pan-Archive discussion,’ recalls McAllen. ‘We had our editorial and curatorial choices, as did MOE. There was considered debate and some to and fro between parties’.

'The exercise was to hold a mirror up to ourselves as a nation and we wanted to get audiences talking,’ explains Wharerau. ‘The footage reflects the language and attitudes at the time. We wanted to present this stuff, whether it was uncomfortable or not’. It’s about creating conversations, he reckons. ‘We’re just putting it here. If we as a country are brave enough to have those discussions, then the video has done its job’.

Attitudes and representation change across decades. This led to conversations about some of the footage and how it flowed. A challenge with using archival material is that it has been removed from the context of when it was first made and screened. Differences in formats raised questions, too – silent material is different to sound or television. And though an item was selected, what part – given time constraints – would best add to the overall story? How do these items best flow together?

The curatorial team considered all this, then worked on refining a narrative that helped to connect all the parts into a wider story. Wharerau remembers that ‘crafting that narrative was just as full-on as selecting material in the first place’.

Still from 'Love and Sacrifice – A Day in the Service of Christ’s Little Ones' - a convent nurse providing drinks for children.

Telling the Story

It was hoped this programme could lead to conversations across generations – it was compiled for ages 11 and up. Wharerau, who also narrates part of the programme, shared it with his 10-year-old granddaughter, daughter and mum, ‘and they all got something out of it. For Mum there were lots of memories. For my daughter there was lots to review. And for my mokopuna, she was amazed, it opened up heaps of stuff she didn’t know about’. His granddaughter needed some explaining however – she was surprised her koro was alive narrating film in 1901!

Still from Te Matakite o Aotearoa – The Māori Land March - a shot of hīko.

A key focus of the project was the representation of the relationship and dual heritage of Māori and non-Māori. The title, Ngā Wai e Rua, references the waters of a braided river. In New Zealand, different people and cultures come together. Though they keep their own identities, the groups flow and mix.

‘We included other cultural groups, but the primary context for the Tuia project was encounters between Māori and Pākehā,’ says McAllen. Wharerau suggests that ‘from a Māori perspective, there is “Māori” and “other”. I see everybody else as a partner (via Te Tiriti). With this partnership, it’s important to have them in the recording’.

Watching the Show

The finished version is a speedy watch with nearly 50 items in its 45 minutes. Many of the items are online in full and viewers are encouraged to engage with parts that caught their attention. But the programme isn’t a history of New Zealand, says McAllen. ‘It’s a compilation or snapshot. We’re not capturing everything but telling the story of what our audiovisual collections can give you’.

'When a City Falls' - members of the Student Volunteer Army helping to shovel away liquifaction in Halswell, Christchurch.

The audiovisual collection is rich and rewarding viewing, but only shows so much. One of the programme notes asks, ‘Who is behind the lens?’ Much of our collections record ‘important’, historical events, but what was important was determined by a very narrow band of people. Groups such as Māori, tau iwi, women and minorities are under-represented or not recorded at all – another curatorial challenge.

The recording ends with footage from When A City Falls, a documentary about the Canterbury earthquakes. ‘While we acknowledge it was a traumatic time, it also looks to the future and thinks about rebuilding,’ says McAllen. ‘There’s a digger driver helping clean up who says something like “this is what we do, we’re New Zealanders”,’ notes Wharerau. ‘It was a national tragedy but we pull together’.

We’re all New Zealanders, wherever we’re from. The mixing waters of a braided river flow and combine, like people in New Zealand being brought together. Our experiences of living here are intimately connected with these groups and our relationships to them. Ngā Wai e Rua aims to get viewers of all ages thinking about this.