Hero image: Shepheard’s Hotel. Via grandhotelsegypt.com

Luggage label issued by Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo, Egypt, ca 1917, designed by Mario Borgoni. Reference PA1-q-604-12a. The Powles Family Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library.

By Sarah Johnston

In both World Wars of the twentieth century, New Zealand forces found themselves fighting in the Middle East. When on leave in Cairo, a fortunate few with sophisticated tastes and cash to spend might have found themselves enjoying a drink at the famed Long Bar or on the terraces of Shepheard’s Hotel, one of the world’s most famous hotels for over 100 years. The 1917 Shepheard’s luggage label above, held in the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library, is testament to the place the hotel held in New Zealand memories, as a moment of respite from war.

Since opening in 1841, Shepheard’s hosted any visitors of note passing through the Egyptian capital. In World War II, it was an alternate HQ for the Allied 8th Army, and when the tide of the North African campaign was in Germany’s favour, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was rumoured to have picked out a room and proclaimed that he would ‘soon be drinking champagne at Shepheard’s.’ Attempting to foil Rommel’s plans was the New Zealand Division, part of the 8th Army. With the 2NZEF was the New Zealand Broadcasting Unit, who in March 1941 found themselves in this legendary establishment to make sound recordings.

From King Farouk of Egypt to the Greek government-in-exile, film stars, archaeologists, Nile explorers and Winston Churchill, Shepheard’s hosted a fascinating array of guests. In 1942, American magazine Life described its colourful clientele:

"The well-to-do British officers in Egypt, the ambassadors with letters plenipotentiary, the Americans with fat purses, the glamor girls of the Middle East, the Russian commissars, the famous war correspondents and the civilian tank experts, all stay at just one hotel in Cairo: Shepheard’s. When the war in the desert went really badly, a favorite criticism back home was that it was being fought from the terrace at Shepheard’s." (1)

New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser would be a guest himself in May 1941, where he was photographed meeting Egyptian Army officials and New Zealand nurses at Shepheard’s.

Prime Minister Peter Fraser with Emily May Nutsey and other nurses at Shepheards Hotel in Cairo, Egypt. Alexander Turnbull Library. DA-01096-F

The 1996 Oscar-winning film The English Patient, based on Michael Ondaatje’s novel of the same name, was set amidst the glamour and intrigue of wartime Shepheard’s. The film’s lead characters, Count Almasy and Katherine Clifton (played by Ralph Fiennes and Kirstin Scott-Thomas) begin their doomed love affair at the hotel (although the scene was actually shot at a hotel in Venice, because the original Shepheard’s was destroyed in 1952).

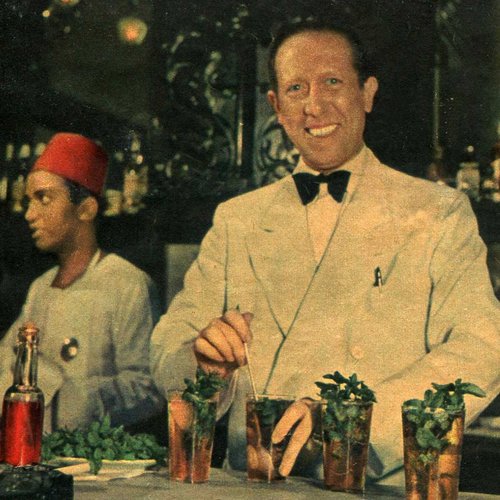

In March 1941, the New Zealand broadcasters would have found Shepheard’s legendary barman Joe Scialom (‘one of the 20th century’s most famous mixologists’ (2) and the world’s most famous barkeep) behind the Long Bar, together with staff dressed in long white robes with red tarboosh hats (fez). Scialom was famed for inventing a cocktail for Allied officers nursing hangovers; the Suffering Bastard, whose name was sometimes sanitised to the Suffering Bar Steward. According to legend (unverifiable), the gin, bourbon, lime juice, mint and ginger beer concoction was such a hit that in 1942 he was asked to send several gallons of the mix out to the Western Desert to fortify men ahead of the Battle of El Alamein. (You can read more about Joe – and his recipe – here).

Joe Scialom at the Long Bar at Shepheard’s Hotel

But in March 1941, El Alamein was still over a year away. A week before this recording session, men of the New Zealand Division had begun departing Egypt for the start of the ill-fated Greece campaign, but military authorities refused to give permission for Noel Palmer, Doug Laurenson and Norman Johnston of the NZBU to join them.

The broadcasting unit’s officer-in-charge, Noel Palmer, campaigned for them to be allowed to go to Greece and report on the New Zealanders in action. His frustration at being left behind at Cairo’s Maadi Camp is revealed in letters to former colleagues at National Broadcasting Service Engineering back in Wellington: ‘We are sitting on our tails at Base. We confidently anticipate “OBE’s” at the end of the war: “Only Been in Egypt,”’ he wrote. (3)

Palmer eventually went as far as getting his request to go to Greece in front of 2NZEF commander General Bernard Freyberg, but the answer was still ‘No’. As it turned out, this was fortunate. The Greek campaign was a disaster and had the NZBU gone with the 2NZEF any recording equipment they took with them would have had to be abandoned in the Allies’ hurried retreat from Greece and Crete. This would likely have spelled the end of the Broadcasting Unit’s work in North Africa.

So it was that the Unit found themselves not in Greece, but cooling their heels at Shepheard’s Hotel, to record a live performance by a dance band as part of the Middle East Forces Programme. This was a radio show for all Allied forces in the region, broadcast daily during the war by Egyptian State Broadcasting and usually presented by the urbane British actor Peter Haddon.

When Haddon was unavailable, the New Zealanders occasionally stepped in to host. The New Zealand, British, Australian and South African broadcasters in Egypt had formed the grandly titled Empire Broadcasting Co-ordinating Committee in late 1940 to pool resources and try and present a united front when dealing with censors and other military authorities. British-run Egyptian State Broadcasting was a particular source of help to them and shared facilities with the New Zealanders and vice versa. ESB was impressed with the custom-built New Zealand recording van brought over from Wellington, and highlighted it in a three-page article about the New Zealanders in its magazine Cairo Calling. (4)

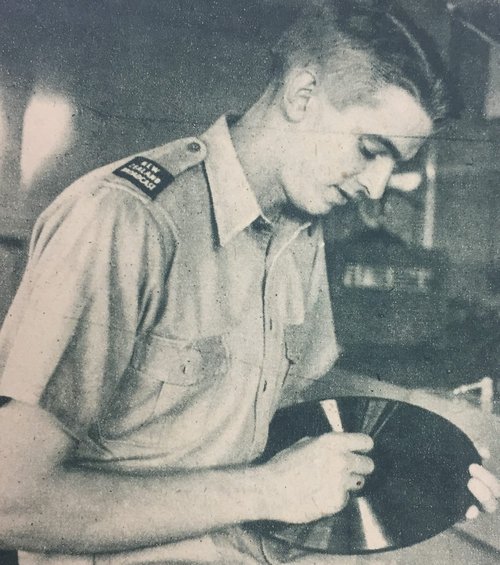

New Zealand Broadcasting Unit assistant engineer Norman “Johnny” Johnston, labelling a lacquer disc [Photograph from “Cairo Calling” – Egyptian State Broadcasting Service magazine, 30 November, 1940. Archives NZ ADQZ 18886 WAII1 R20107884]

The Middle East Forces Programme was ‘one radio show to which all New Zealanders tune in, if they are within five miles of a radio set,’ Doug Laurenson reported in his introduction to a short talk by Peter Haddon for broadcast back in New Zealand in February 1941. An ebullient Haddon tells Kiwi radio listeners that he has enjoyed building the programme for their men in the Middle East, even though he had few resources except a ‘bucket-load of enthusiasm and a basin-full of goodwill.’ They broadcast for an hour every day: 15 minutes dedicated to Indian troops and the rest to British forces (which included the New Zealanders). The show was mostly musical entertainment – often performances by the troops themselves. Haddon pays warm tribute to the New Zealand Broadcasting Unit in his talk, saying the success of the programme was largely due to their support, as he initially had no radio experience: “They took one look at me and didn’t know whether to laugh or cry,’ he jokes. (5)

In order to give home-front radio listeners a taste of what their husbands, sons and sweethearts were listening to in Egypt, the NZBU recorded a Middle East Forces session that they presented – and it includes the relay from Shepheard’s Hotel. A portion of the programme survives on discs in the RNZ Sound Archives at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision. The discs were sent back to Wellington from Cairo and would have aired at home in the weekly radio programme With the Boys Overseas, which played on Sunday nights throughout the war.

Listening to them transports you to Shepheard’s palm-lined ballroom. ‘Hello Middle East,’ begins announcer Doug Laurenson. ‘We are on relay from Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo.’ (6) He describes the hotel and reassures New Zealand listeners that those who fondly remember Shepheard’s from their time in Egypt in World War I will find it has changed little since then. In what may be an oblique reference to the New Zealand troops now tuning in from Greece, he also acknowledges ‘those listening in from another country, not in the Middle East.’ Military censorship would have prevented him making any direct reference to the fact that, as he spoke, several thousand New Zealanders were in the process of joining the British and Australian forces assembled in Greece.

Doug then introduces the dance band for the broadcast, The Continental Savoy Orchestra, under bandleader Maio Reiniger. The band is to play some popular dance numbers, with new arrangements ‘just arrived from America.’ The first is Louis Armstrong’s 1936 composition “Swing that Music,” followed by “Mary Lou,” a 1920s hit.

Sadly those two numbers are all that survive in the Archives of that broadcast from Shepheard’s, but if you fancy time-travel to wartime Cairo, shake up one of Joe Scialom’s ‘Suffering Bar Steward’ cocktails, tune in to the Continental Savoy Orchestra via the online recordings on the Ngā Taonga website, and browse the 1936 book Story of a Historic Hostelry.

References

- 1. Robert Landry, Life magazine, 14 December 1942. Cited in Shepheard’s Hotel: the British base in Cairo

- 2. Joe Scialom, Cocktail Kingdom

- 3. Noel Palmer to J.R. Smith, 14 April 1941. Accounts Correspondence received from the Broadcasting unit with 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force Box 37c Record no. 2/4/43, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 4. “New Zealand Broadcast ‘, Cairo Calling, November 30, 1940. 2NZEF – Public Relations Service – Broadcasting Unit – General Box 52/ Record No. DA 8/9/10/1 Part 2, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- 5. Peter Haddon in U-series. Here, There and Everywhere, Parts 12 and 13, ID1183-4 Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision, Wellington

- 6. U-series. Portion of Forces Programme Parts 1-3, ID11914, 11916, 11917 Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision, Wellington

About the author

Sarah Johnston is a former broadcaster and sound archivist, researching recordings made by the New Zealand mobile broadcasting units during World War II. You can read more about the project on her blog World War Voices.